Early commercial radio stations valued listener reports, as they were the major means by which broadcasters could tell if and where their programming was being received. The reports helped station marketers develop demographics for the station in general, and for specific programming.

Telephone calls from listeners helped, but a penny post card pre-addressed and asking the listener to fill in perhaps two or three pieces of information pulled more responses than inviting folks to call in.

In contrast, a telephone call cost more than a penny — a lot more if you were calling long-distance from your small town to powerhouse stations like WSM in Nashville, WLS in Chicago, WLW in Cincinnati, KDK in Los Angeles, or any of the other stations heard hundreds — or thousands — of miles from their transmitters and antennas. Plus, not everyone had telephone service in the 1920s.

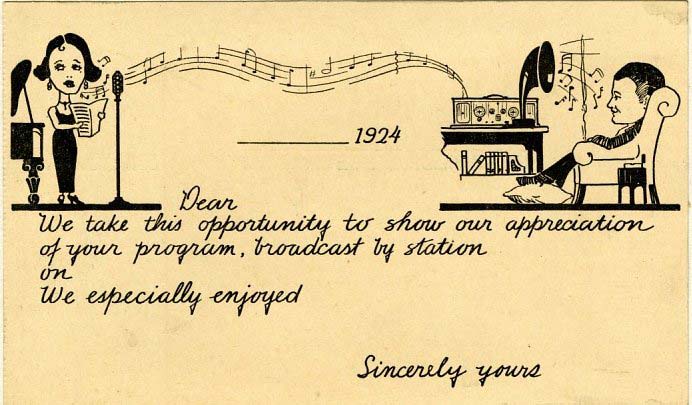

Thus, the penny postcard quickly became the preferred medium for listener reports. A typical report consisted of the date and time, the station call letters along with the name of the show received, and a brief comment or two — all of which would easily fit on a postcard.

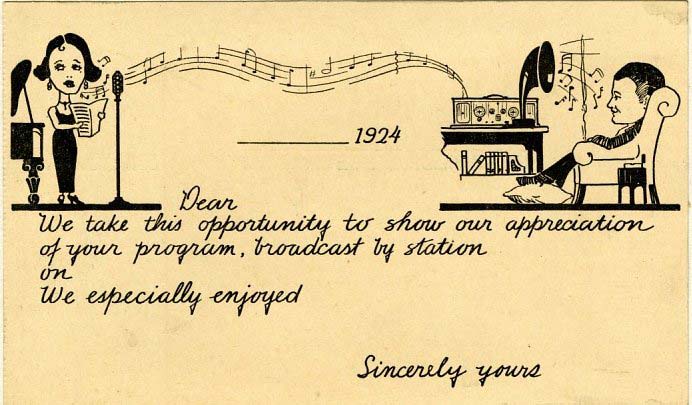

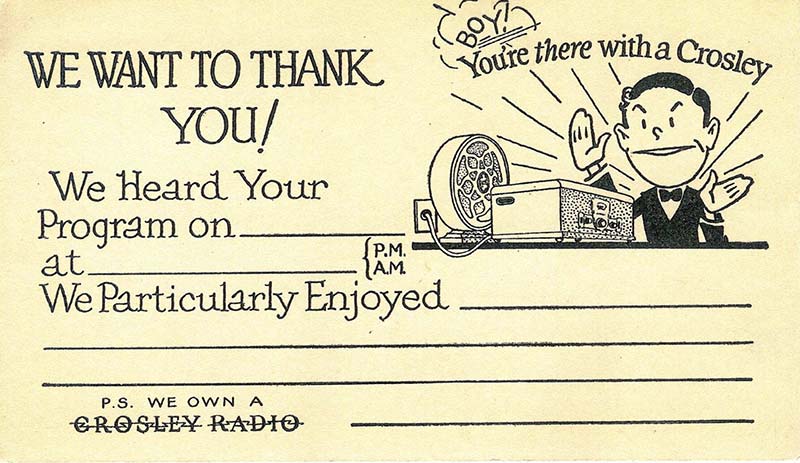

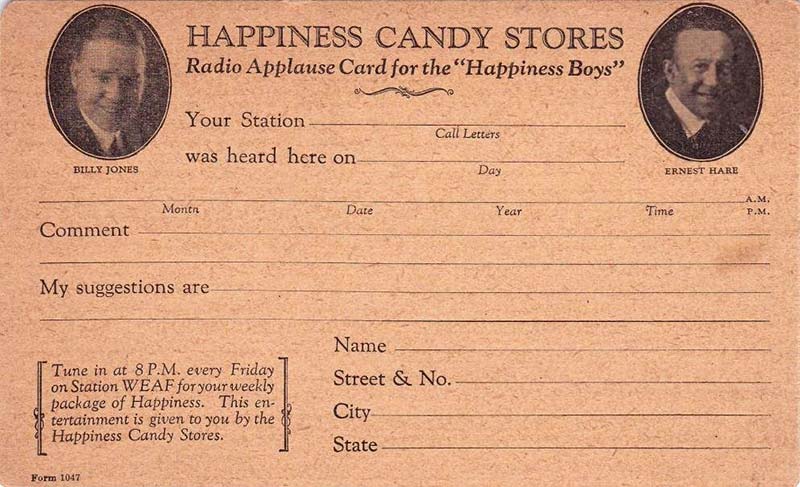

The cards became known as “applause cards” because they conveyed appreciation for a station or specific show. Pre-printed applause cards began showing up in 1923, distributed by radio stations, manufacturers, and other commercial entities. As shown in Figure 1, these cards were miniature forms.

FIGURE 1. A typical pre-printed applause card.

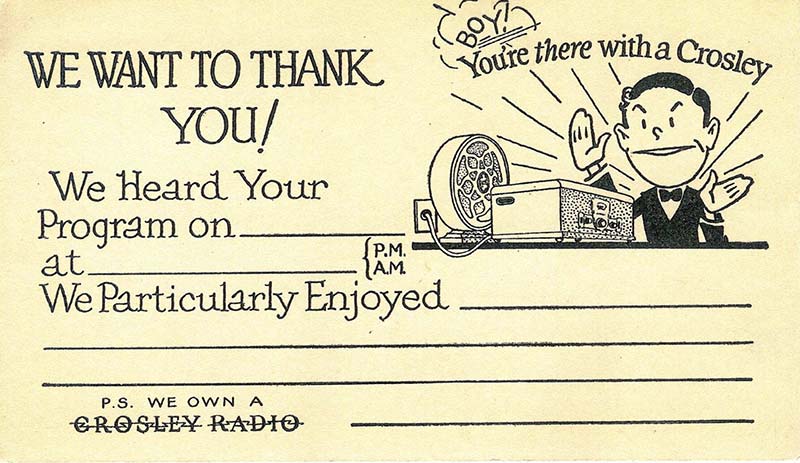

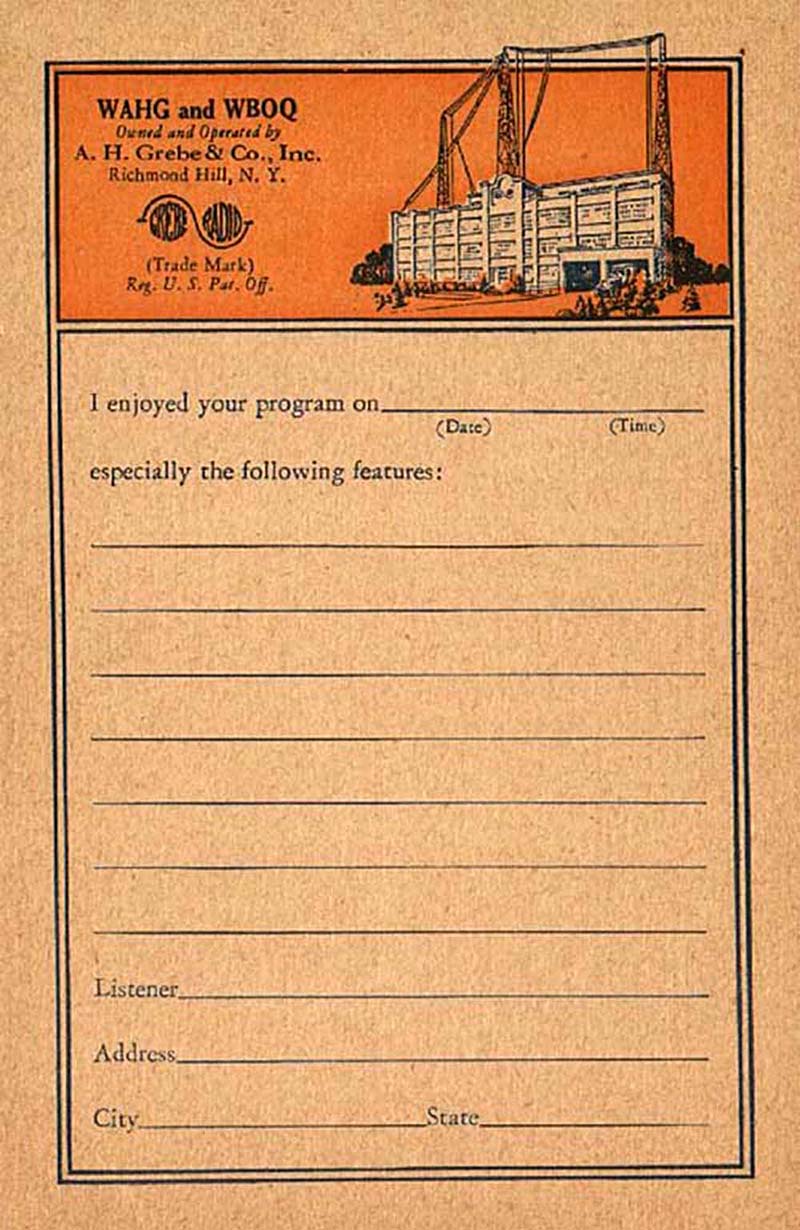

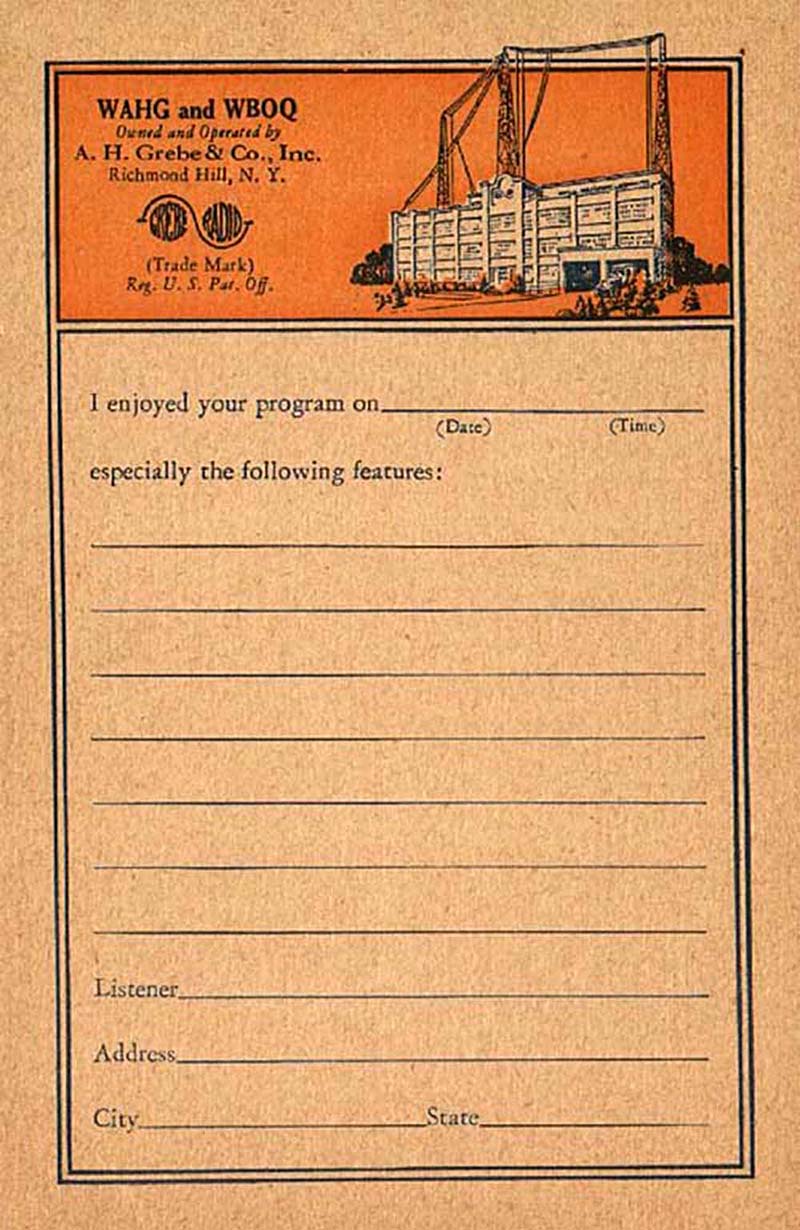

Radio manufacturers such as Crosley (Figure 2) and Grebe (Figure 3) packed several applause cards with each new set. As seen in the accompanying illustrations, manufacturer applause cards promoted the brand providing them, just as station cards promoted the station and sometimes specific shows.

FIGURE 2. Crosley Radio applause card.

FIGURE 3. Applause card for A.H. Grebe Company’s stations.

Crosley took things a step farther. In an envelope that contained applause cards, the company included several “invitation cards” for new Crosley owners to use to invite their friends over for a radio party (a popular urban event in the early 1920s). Refer to Figure 4.

FIGURE 4. Crosley Radio applause cards like this one enlisted the new owner to help sell more Crosley sets.

As can be seen, these cards also plugged Crosley sets, hopefully encouraging the friends of the new radio owners to buy the same.

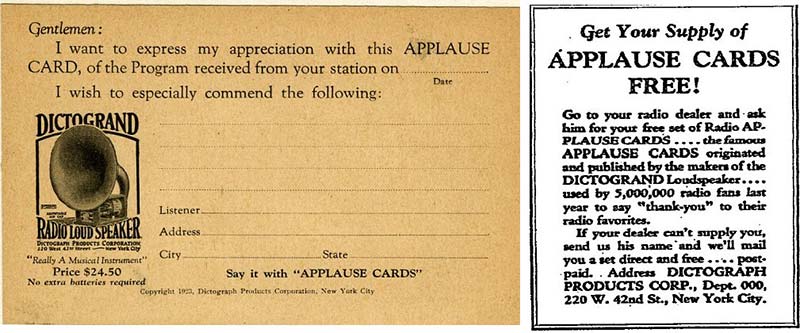

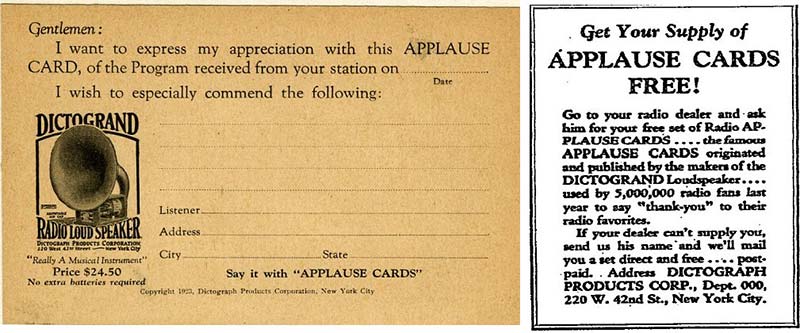

Applause cards were also distributed by radio dealers, sometimes on behalf of manufacturers. The Dictograph Company, which made radio speakers, headsets, and other equipment, distributed applause cards through its dealers. Dictograph newspaper ads (Figure 5) encouraged the public to come into their local radio shop and load up for free, as shown in the accompanying newspaper ad from 1924 in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5. Applause cards were often combined with other media (a newspaper ad in this instance) to cross-promote products.

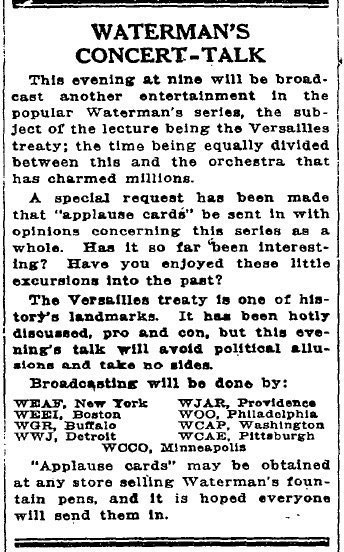

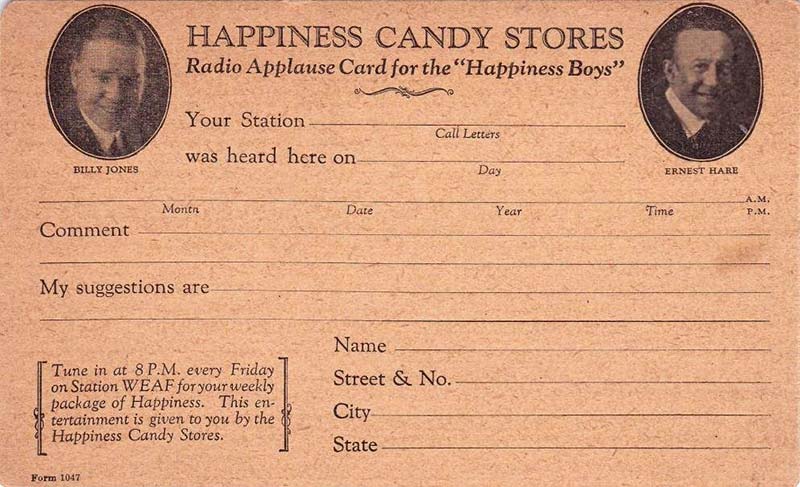

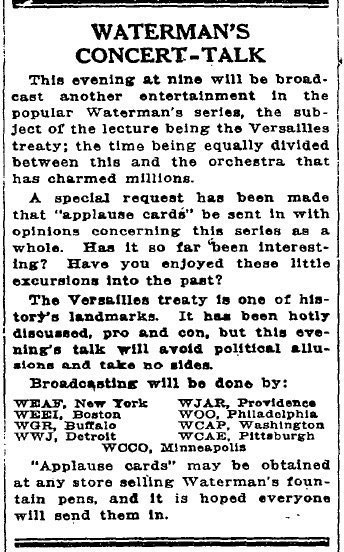

Sometimes, the cards were used to advertise non-radio goods, usually by companies that sponsored radio programs. Among others, the Waterman Ink Pen Company (Figure 6) and Happiness Candy Stores (Figure 7) distributed free applause cards through their retailers.

FIGURE 6. Waterman Ink Pen Company newspaper ads informed the reader and offered applause cards.

FIGURE 7. Happiness Candy stores promoted their product, stores, and radio shows with applause cards.

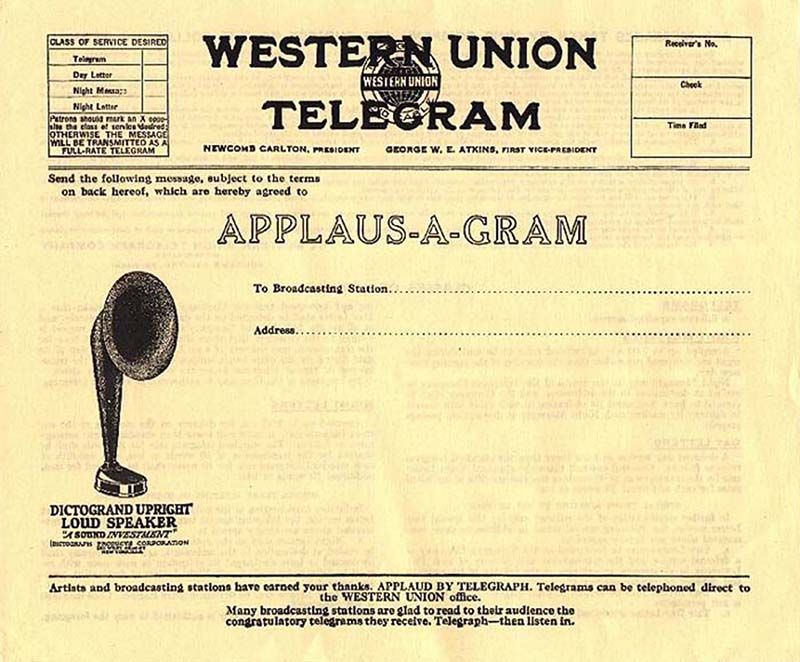

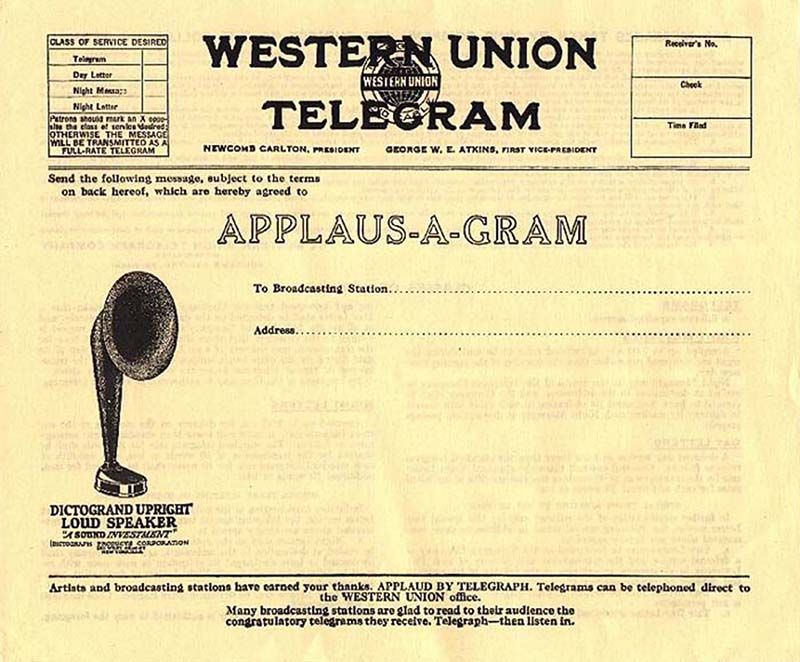

For instant gratification, dedicated fans could send a Western Union APPLAUS-A-GRAM (Figure 8) and hang the expense!

FIGURE 8. Those who really cared could express their appreciation for a station, program, or performer with a Western Union APPLAUS-A-GRAM. (Note the Dictograph ad at left on the APPLAUS-A-GRAM.)

Radio applause cards were a relatively short-lived phenomenon. They came into existence just as radio began to boom in the early 1920s and lasted until 1926, by which time radio was no longer the novelty it once was, and stations began relying on professional surveys, advertiser results, and other means of gauging the extent and demographics of their audiences. NV