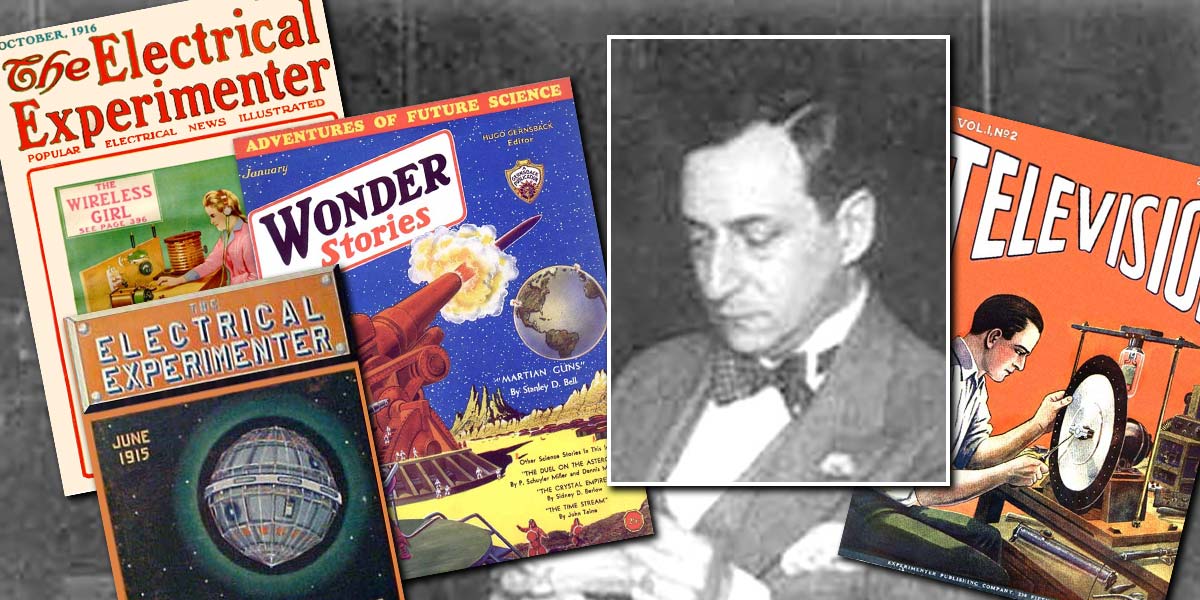

Who was Hugo Gernsback? The answer depends on whom you ask. “Gernsback published the first science fiction magazine!” a science fiction reader will declare. Ask an engineer and you might hear, “Gernsback ... wasn’t he involved in early experiments with television broadcasting?” Others will recall Gernsback’s radio magazines. A radio historian will tell you that Hugo Gernsback owned radio station WRNY, introduced the first home radio set (1905), and championed the cause of radio amateurs.

A scattered life, indeed, but with one with a focus: the future. Hugo Gernsback was the world’s first futurist — one who not only speculated about the future, but also worked to make it happen.

Born Hugo Gernsbacher on August 16, 1884, Gernsback was the son of a vintner in Luxembourg. As a child, he became fascinated by electricity when a handyman at his father’s winery showed him how to wire a battery to a bell to make it ring.

Gernsback almost immediately expanded his capabilities with battery powered telephone sets, lights, and buzzers. He wired the family home with telephone-intercoms and a 6 volt lighting system. He was soon installing door buzzers and intercoms in neighbors’ homes and was commissioned to set up a complicated system of buzzers in a nearby convent.

When he was 10, Gernsback experienced a bizarre event. After reading American astronomer Percival Lowell’s book about Mars, he was so overwhelmed by the possibility of life on the Red Planet that he fell into a two-day delirium, babbling incessantly about Martians and their technology. This obsession shaped his life.

Following his basic education, Gernsback was enrolled in a boarding school in Brussels. He mastered all he studied, including English. He read Western novels, including the works of Mark Twain, which fueled a desire to go to America.

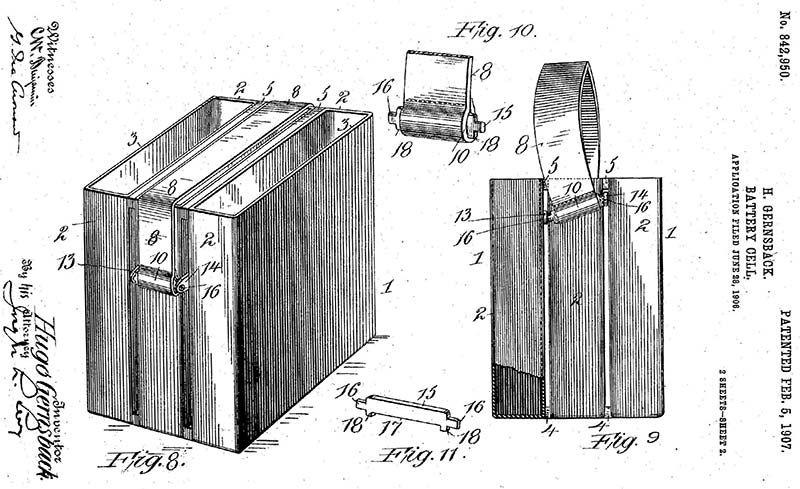

Gernsback next studied electrical engineering in Germany, where he perfected a portable radio-telegraph transmitter and a high amperage, dry-cell battery that he was convinced would make him rich. In 1904, he bought a first class ticket to Hoboken, NJ, taking with him two models of his battery and $100.00 from his family.

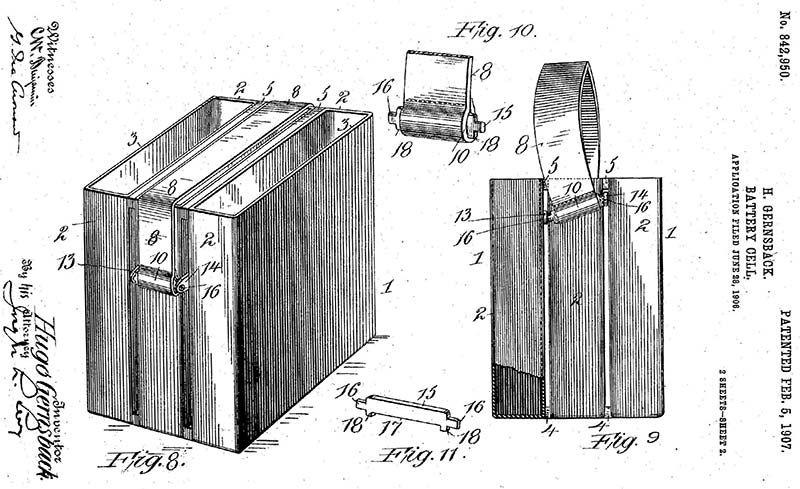

The young man made his way to New York, where he distributed business cards with the name “Huck Gernsbacher.” (He borrowed the name from his favorite character, Huckleberry Finn). After receiving US patent #842,950 for his battery, he sold the rights to the Packard Motor Company.

Hugo Gernsback’s first patent, filed in 1906 for a storage battery.

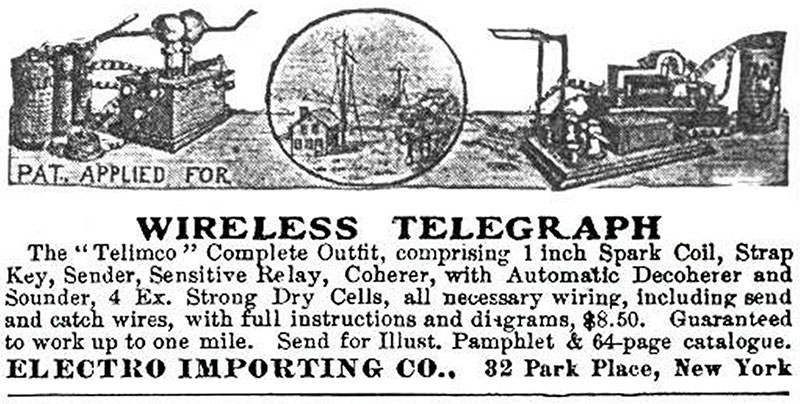

Now flush with cash, Gernsback decided to build and market his portable radio transmitter. Unable to find the parts he had used in Europe, he ordered them from a German supplier, at which point it occurred to him that perhaps there was money in importing radio components. He found an investor/partner, Lewis A. Coggeshall, and they rented space in a building at 32 Park Place in New York, where they established the Electro Importing Company to sell radio components and electrical supplies by mail order.

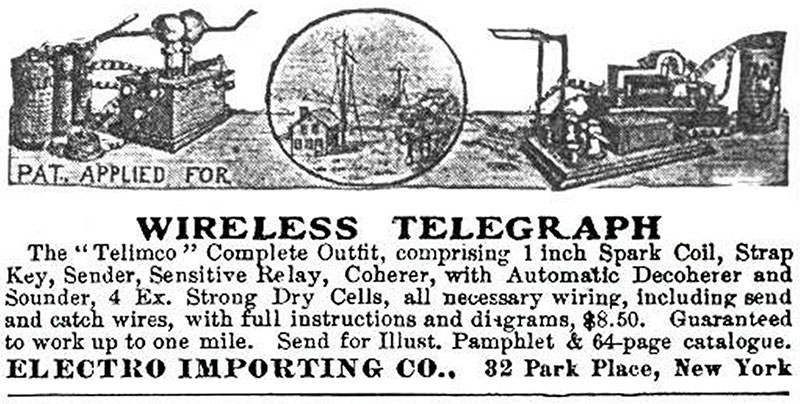

Gernsback’s spark gap transmitter came with a receiver and had a one mile range. Marketed as the “Telimco Wireless Telegraph,” it sold for $8.50. (“Telimco” was derived from the company’s name.) This was the world’s very first home radio set.

The first ad for the Electro Importing Company’s “Telimco” wireless radio-telegraph transmitter and receiver, which appeared in Scientific American in 1906.

Scientific American published an article about the Telimco in 1905, but sales didn’t take off until 1906, when Gernsback placed ads in Scientific American, Youth’s Companion, and The New York Times. The set was copied by competitors — but not before Gernsback sold Gimball’s, Macy’s, and Marshall Field on carrying it.

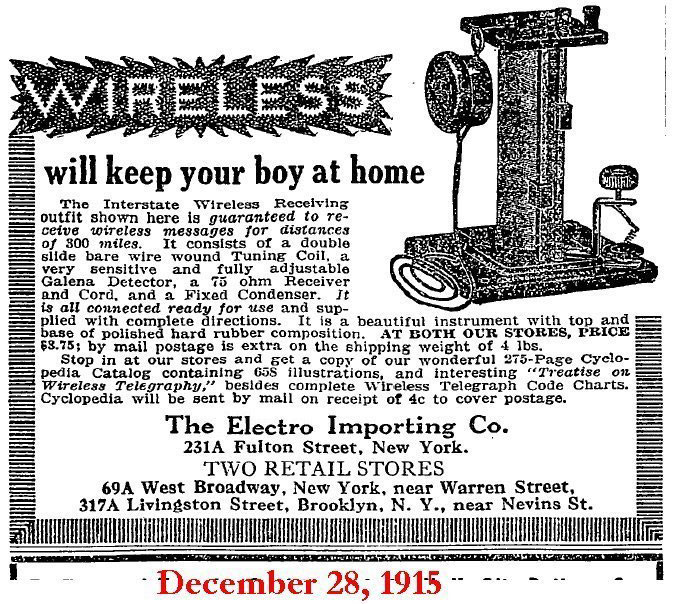

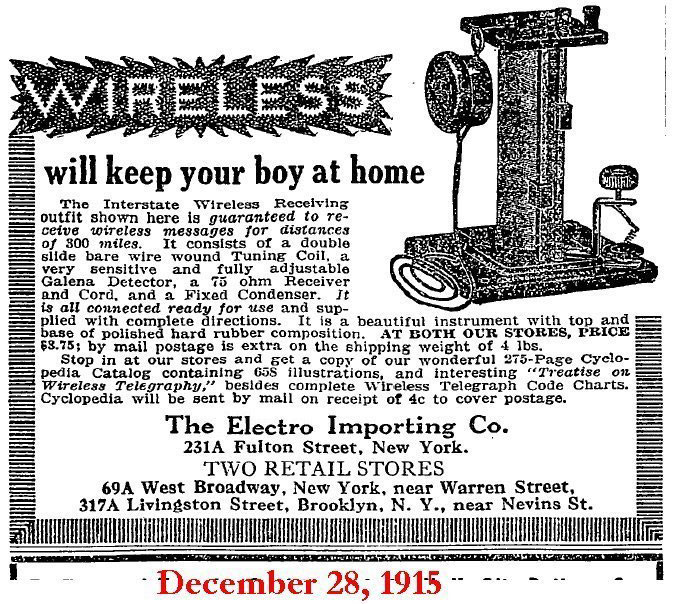

In addition to the Telimco, the company offered coherers, “Telimphones,” spark gaps, wire, and batteries. Whenever possible, Gernsback presented radio as a wholesome activity; ads for the Telimco proclaimed that, “Wireless will keep your boy at home!”

“Wireless will keep your boy at home,” advised a 1915 advertisement from Gernsback’s Electro Importing Company.

Demand mushroomed. Within two years, the Electro Importing Company was sending its 64-page catalog throughout North America. (Even Lee De Forest shopped Electro Importing!)

Gernsback didn’t hesitate to flaunt his success, wearing tailor-made suits, expensive shirts, and a monocle, while affecting the manners and attitudes of European gentry. He dined at New York’s most expensive restaurants and was seen at the best theaters. Not surprisingly, he soon married a young woman named Rose Harvey. She bore him a daughter in 1909. (He would marry twice more and father a son and another daughter.)

Hugo Gernsback in the flamboyant, aristocratic persona he presented to the world.

The Gernsback-Coggeshall partnership dissolved in 1908. January 1909 found Gernsback running this ad in The New York Times:

Partner wanted in well-established electrical

manufacturing business; good chance for right

party; have more orders than can fill;

only parties with sufficient capital need apply.

H. Gernsback, 108 Duane St.

The ad was answered by a man named Milton Hymes. With the infusion of capital, the company moved its factory and 60 employees to 231 Fulton Street in New York and soon opened two retail stores.

Gernsback wrote lengthy tutorial articles for the Electro Importing catalog. This gave him the idea of starting a magazine for electrical experimenters, which he called Modern Electrics. The magazine quickly established itself as a cutting edge publication; the December 1909 issue carried an article by Gernsback titled “Television and the Telephot,” which was the first instance of “television” being used in a technical article. (Gernsback maintained that a French author had used the term before him, however.)

Gernsback was publisher, editor, chief writer, and often ghost-writer of Modern Electrics and did the layouts and sold advertising. To further promote radio and his magazines, Gernsback established a Blue Book of Radio and the Wireless Association of America (WAOA). WAOA soon claimed 22,300 members and Gernsback worked to represent the interests of amateur radio operators in Washington D.C., helping shape the Radio Act of 1912.

One day in 1911, Gernsback needed to fill some empty space in the issue of Modern Electrics he was preparing. Readers enjoyed his forecasts about the future of technology, so he decided to give them more of the same — in the form of an adventure tale set in the year 2660. He wrote only enough to fill the empty space and ended with a cliff-hanger.

The tale, titled “Ralph 124C41+” (a bit of wordplay) grew to 12 installments. (It was eventually published in book form and remains in print today.) Gernsback soon added science-oriented adventure tales to all his magazines — some written by Gernsback under pseudonyms.

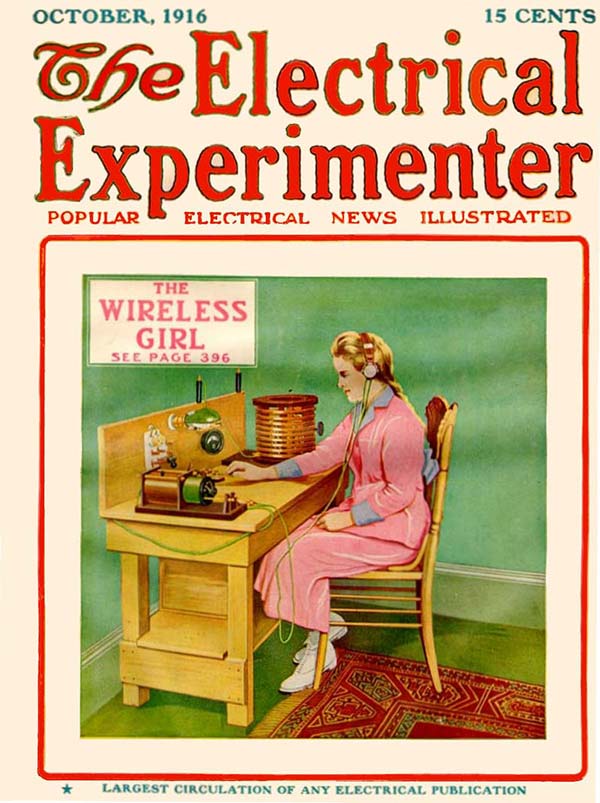

A new magazine called Electrical Experimenter served as another platform for Gernsback to push the science of the future. Complementing this was an irregular series of more Gernsback science fiction stories, called Baron Munchhausen’s New Scientific Adventures.

A typical futuristic Gernsback magazine cover, this 1915 one depicted a satellite orbiting the moon.

When the US government banned amateur radio at the beginning of World War I, Gernsback’s radio business was nearly wiped out. He was stuck with $100,000.00 in radio parts that he could not sell — until he came up with a clever idea. He designed electrical kits based on the parts in his warehouse. Each $5.00 kit came with instructions and all the parts necessary to build a given device. Before long, thousands of experimenters were building such gadgets as “electric fish” and telephone sets. When amateur radio was revived in 1919, Gernsback launched the first magazine devoted to radio, Radio Amateur News.

While Gernsback found it easy to describe his ideas in print, he developed few; details bored him and some ideas were too broad or impractical. For example, he proposed that automobiles be made extremely narrow, with one wheel in the front and one in the rear. Such automobiles, Gernsback said, would solve parking problems. Another space-saving idea was to eliminate cemeteries by launching the bodies of the deceased into space.

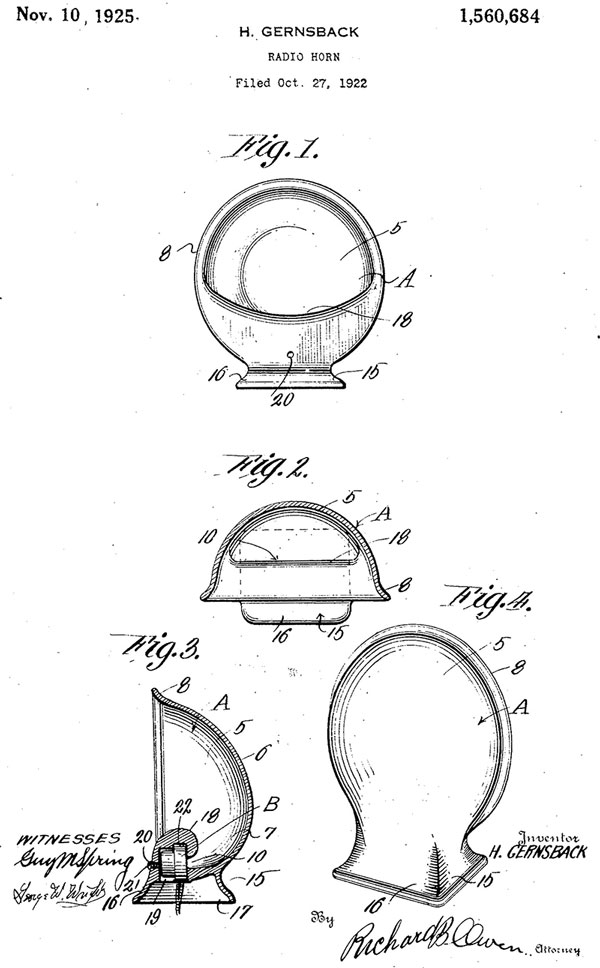

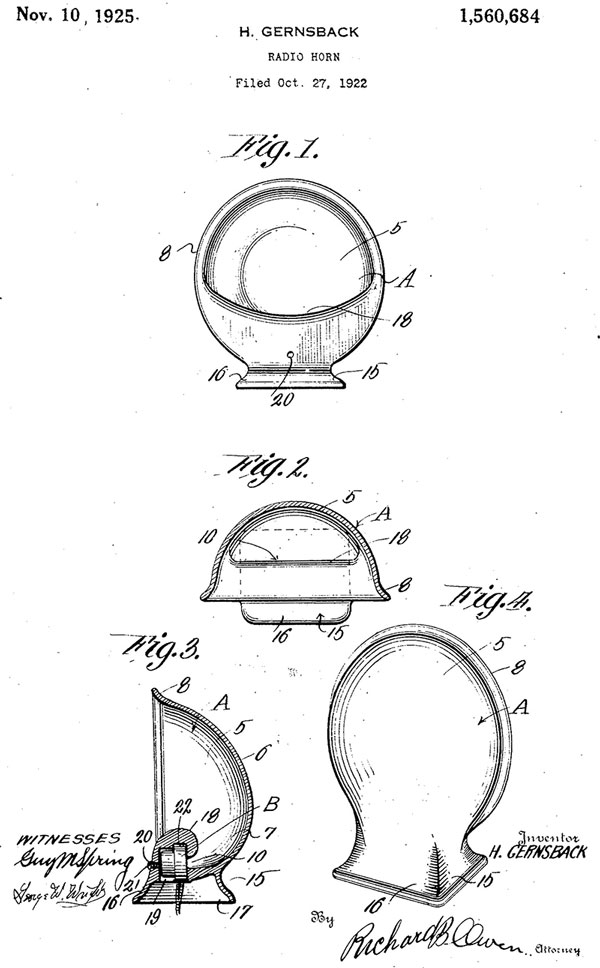

Still, he did have some practical ideas. He patented a new kind of variable condenser that operated on a compression principle; this one earned him some money. A radio speaker patterned after the human ear and several telephone-related inventions followed. (An oft-repeated tale about Powel Crosley “stealing” Gernsback’s condenser is false. Crosley filed a patent for a “book condenser” in 1921. Gernsback filed the patent for the compression condenser in 1923.)

A Gernsback design for a new kind of radio horn speaker in 1922.

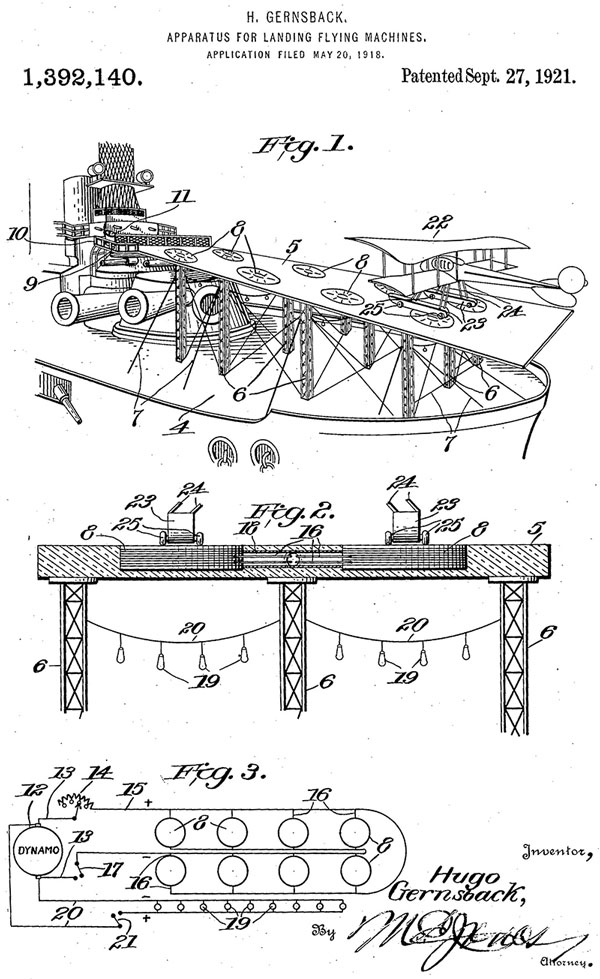

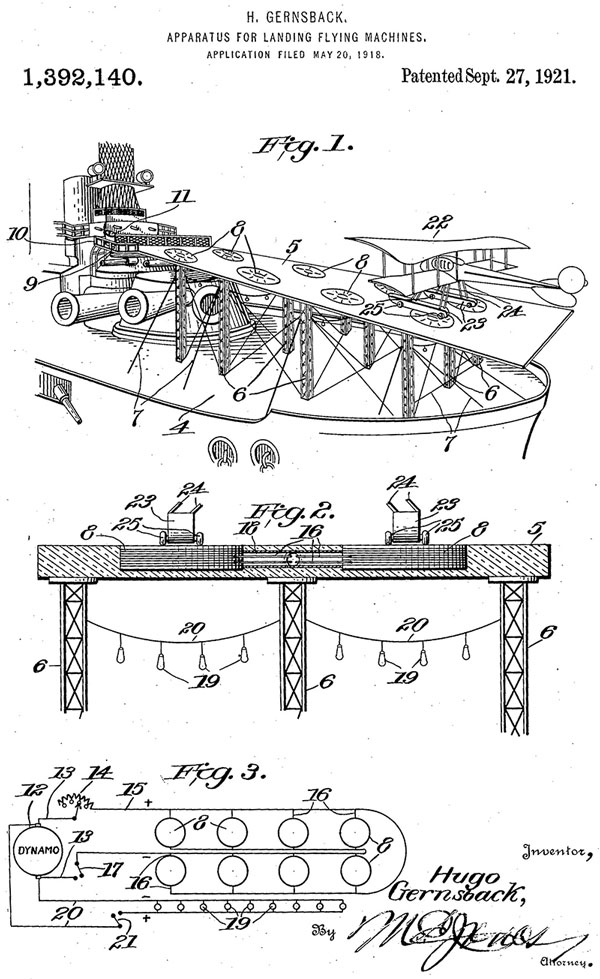

Also among Gernsback’s ideas was a gadget called the “Ososphone,” designed to enable the hard-of-hearing to hear through their teeth via bone conduction. Then, there was a ferris wheel with a twist; instead of merely rotating, it would roll down a track into the Atlantic Ocean, dunking and raising passengers in sealed cabins as it went. He patented this “submersible amusement device” in 1921, along with an idea for landing airplanes on the decks of ships or the tops of Manhattan skyscrapers (giant electro-magnets would insure safe landings).

Another Gernsback patent, titled “Apparatus for Landing Flying Machines,” 1918.

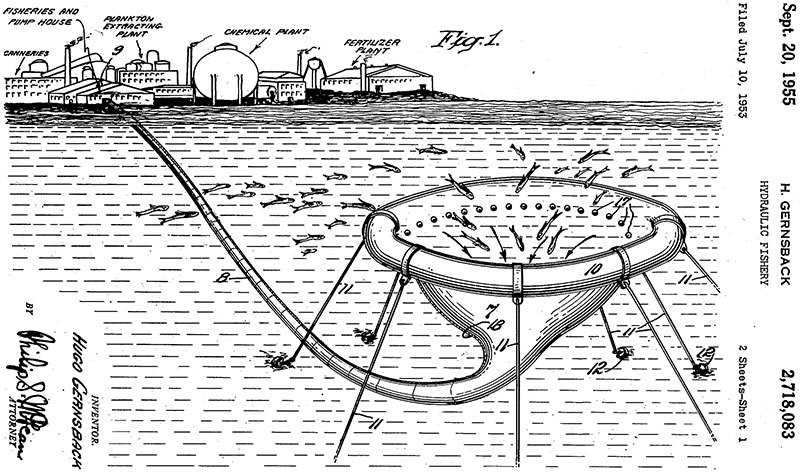

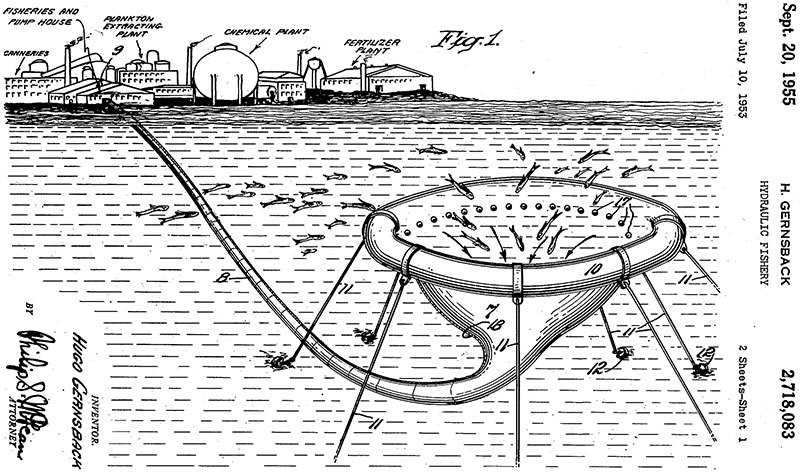

Neither made it to reality, nor did a gargantuan vacuum cleaner-like device designed to suck up schools of fish for commercial processing.

A patent drawing for one of Hugo Gernsback’s many inventions — a “hydraulic fishery” — intended to solve the world’s food problems.

By 1924, Gernsback had started several more magazines: Practical Electrics, Radio Amateur News, Your Body, Science and Invention (formerly Electrical Experimenter), and Radio International. He also published technical books with titles like Radios for All.

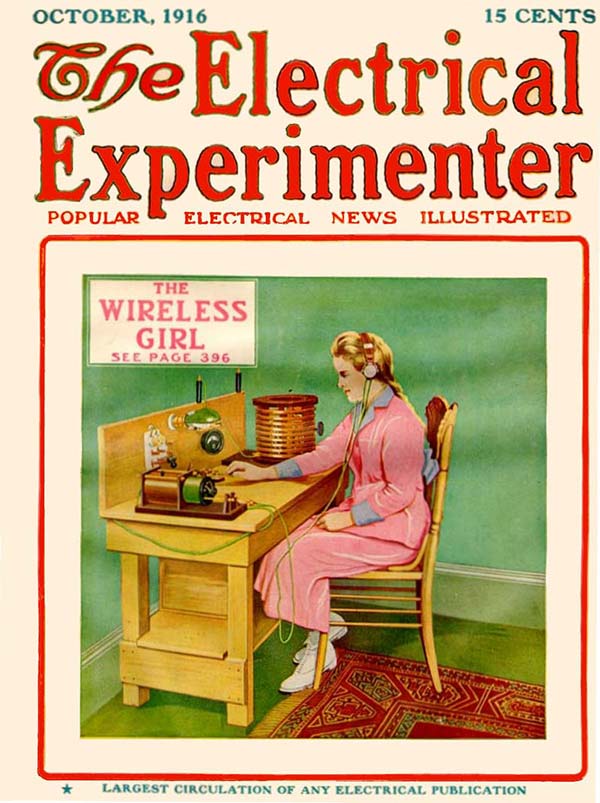

One of The Electrical Experimenter’s more progressive covers.

In the course of promoting the future, Gernsback had become acquainted with many of the world’s leading scientists. His position as a publisher gained the attention of Marconi, Goddard, Tesla, and even Edison. (He was in literal awe of Tesla, whose ideas he viewed as mankind’s salvation. When Tesla died, Gernsback commissioned a death mask of him and published photos of it.)

With his Experimenter Publishing Company providing a healthy cash flow, Gernsback took the obvious next step and moved into broadcasting. Early in 1925, he and a partner, Robert W. DeMott, were granted a commercial broadcasting license and assigned the call sign WRNY. Transmitting at 1160 kilocycles, the station went on the air on June 12, 1925, from a studio in New York’s Roosevelt Hotel. The 500 watt transmitter was located near Coytesville, NJ. Lee De Forest was among the inaugural speakers.

Hugo Gernsback in his office, mid-1920s.

Gernsback also used WRNY to promote his ideas about the future with scientific lectures. Actually, it often seemed that he talked and wrote of nothing but the future and he was fond of making bold prognostications — many of which were accurate. Among other wonders, he predicted microfilm, computer dating, night baseball, cell phones, virtual reality, and flat-screen television. Conscious of his audience, he tempered speculation with articles such as “Electrifying the Holy Land” and “Radio Telephony and the Airplane.”

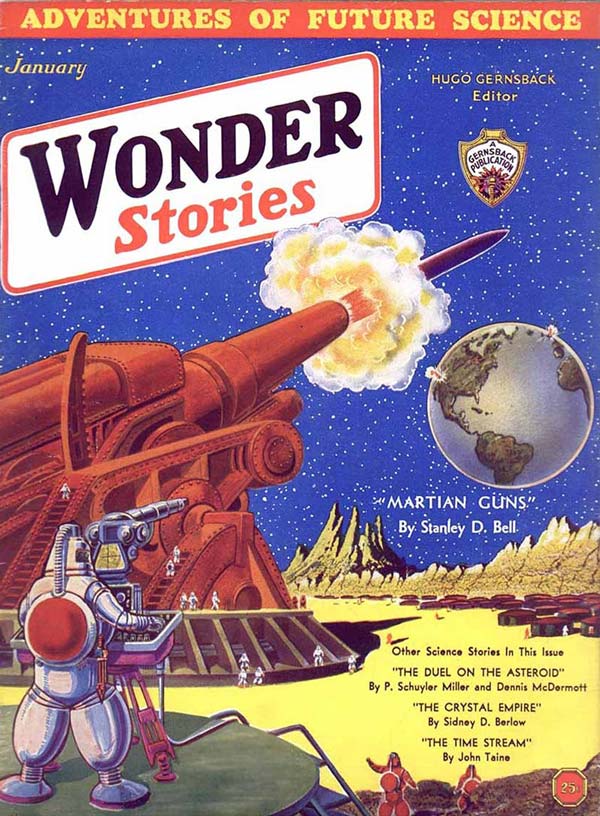

Still, reader response to speculative material in his technical magazines had given Gernsback the idea that there might be a market for science-based fiction. He tested this idea with an all-fiction issue of Science and Invention. Readers demanded more and Gernsback decided to publish an all-fiction magazine called Amazing Stories. The magazine’s motto was, “Extravagant Fiction Today ... Cold Fact Tomorrow.”

Amazing Stories was difficult to categorize. The term “science fiction” did not exist; tales like Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea were referred to as “scientific romances” or simply “adventure.” Gernsback decided that, because the fiction was scientific, he would call the genre “scientifiction.” This evolved into the easier to pronounce “science fiction.”

The first Amazing Stories was published in April 1926. Early on, it carried mostly reprints from the likes of Verne and Wells, but soon switched to all original fiction. Gernsback wasn’t exactly generous to his writers, though. He offered payment as low as 1/4 cent per word for stories and was usually slow to pay. This cost him contributions from several noted writers.

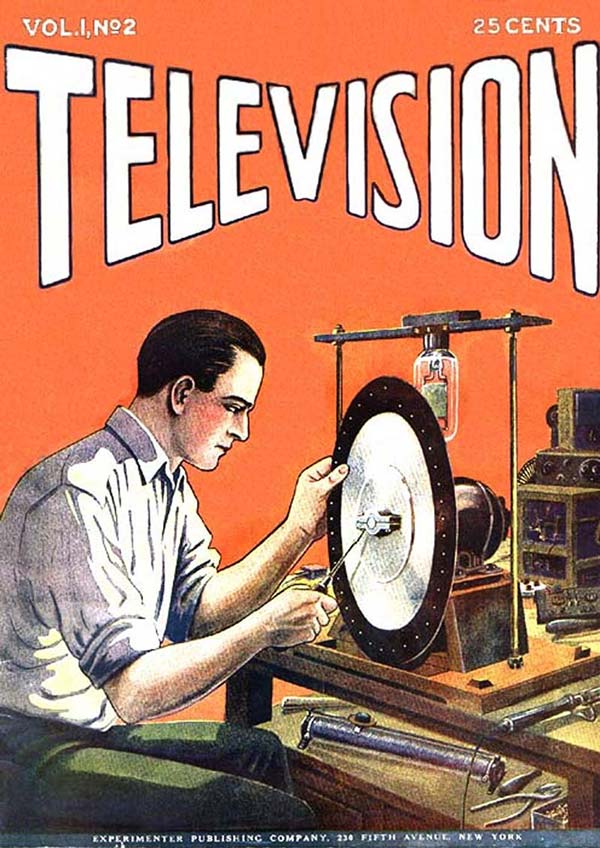

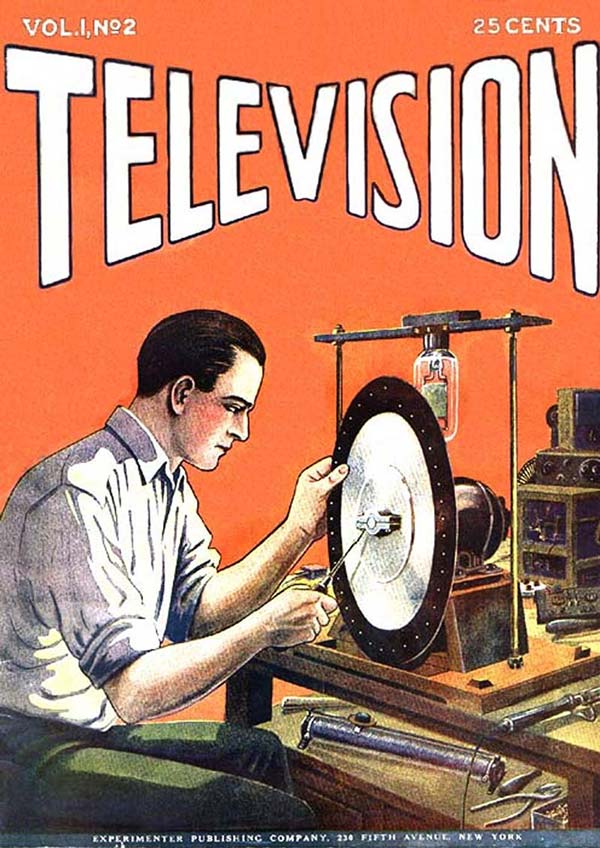

Perhaps Gernsback’s greatest technological achievement was in early television. In mid-August of 1928, WRNY began regular television broadcasts with a mechanical system devised by John Geloso of the Pilot Electric Company. The system used 24 inch, 48 line scanning disks that rotated at 240 rpm. Gernsback published plans for a receiver in Science and Invention and invited radio amateurs to tune in to daily five minute broadcasts. His newest magazine, Television, estimated that there were some 2,000 viewers that summer.

One of the first magazines about television was Hugo Gernsback’s Television.

Just as Gernsback’s publishing empire reached its peak, disaster struck. Like many publishers, Gernsback paid for printing the current issues of his magazines only after receiving the revenues from the preceding issues. A larger competitor convinced printers and other creditors to demand immediate payment, which forced Gernsback into bankruptcy. Unwilling to give up, he sold the Electro Importing Company and WRNY to stake a new publishing company.

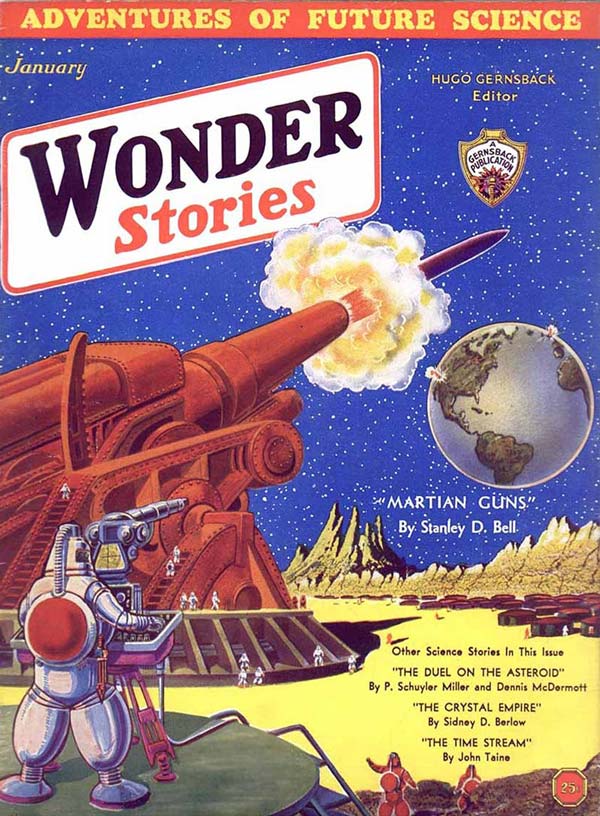

The new magazines competed successfully with his old titles and he expanded with periodicals that reflected his scientific and sociological interests, as well as a few odd subjects, like risqué humor. A partial list includes: Aviation Mechanics, Fotocraft, French Humor, Know Yourself, Motor Camper and Tourist, Popular Electronics, Science Wonder Stories, Scientific Detective, Sexology, Technocracy Review, Woman’s Digest, and Your Dreams. Books for electronics experimenters and professionals continued to come out under the Gernsback imprint, as did science fiction novels.

Air Wonder Stories was Gernsback’s “comeback” magazine after being forced into bankruptcy.

As an inventor, engineer, designer, businessman, writer, editor, and publisher, Hugo Gernsback’s activities touched the lives of millions. It is safe to say that many thousands of today’s broadcast and computer engineers and technicians were avid readers of Gernsback magazines and books early in their careers. The same can be said of science fiction fans.

Gernsback’s accomplishments did not go unrecognized. He is widely lauded as the “Father of Science Fiction” (though “Science Fiction’s Rich Uncle” is more accurate). The World Science Fiction Society’s Annual Achievement Awards are called “Hugos” in his honor. He is also a member of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, the Consumer Electronics Association’s Hall of Fame, and has been similarly honored by other organizations. His homeland applauded his achievements when, in 1954, Gernsback was named an “Officer of the Oaken Crown” by Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg.

Hugo Gernsback went into semi-retirement in the 1950s and continued to promote the future — even publishing an annual booklet of predictions titled Forecasts, which he sent out as a New Year’s greeting. He passed away in 1967 at the age of 83.

Gernsback Publications lived on for three decades. Appropriately, a Gernsback magazine was on the scene when the first personal computer made its debut in 1974; Radio-Electronics featured the Mark-8 minicomputer on the cover of its July 1974 issue. The last electronics magazine connected with Gernsback, Poptronics, lived on until January 2003, when it ceased print publication, but, in a way, at least one of Gernsback’s publications lives on. After several name changes, Gernsback’s first magazine, Modern Electrics, was eventually merged into Popular Mechanics.

On the science fiction side, while Amazing Stories and Air Wonder Stories have breathed their last, Gernsback’s legacy lives on in every science fiction magazine published. Hugo Gernsback’s real legacy, however, is the future. NV