Recap

In our last episode, we started work on the avrtoolbox to help us keep Smiley’s Workshop a bit tidier by providing a clean and orderly place to put stuff. We learned how to document our code with Doxygen and how to keep track of all those functions lying around by putting them in libraries.

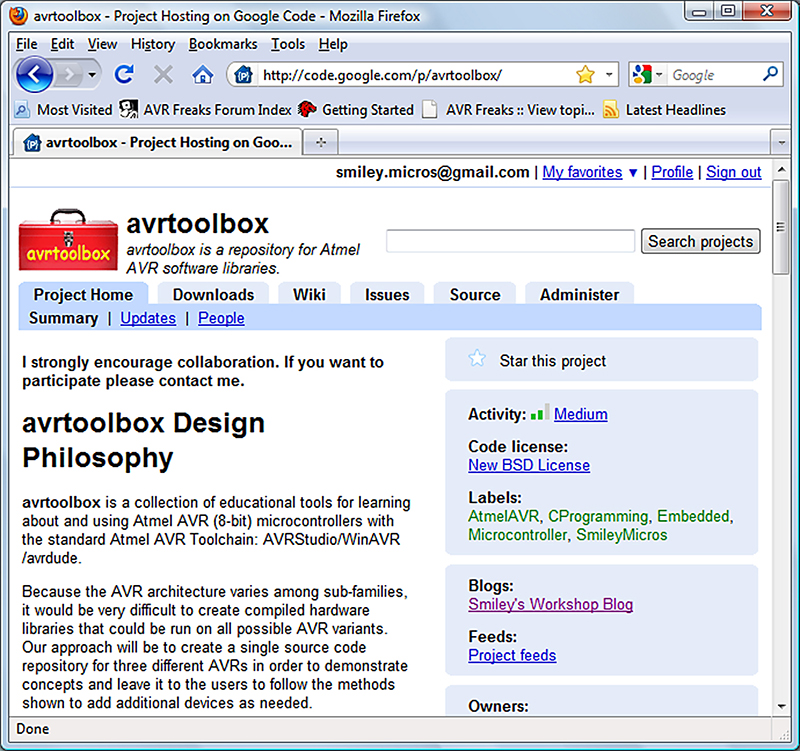

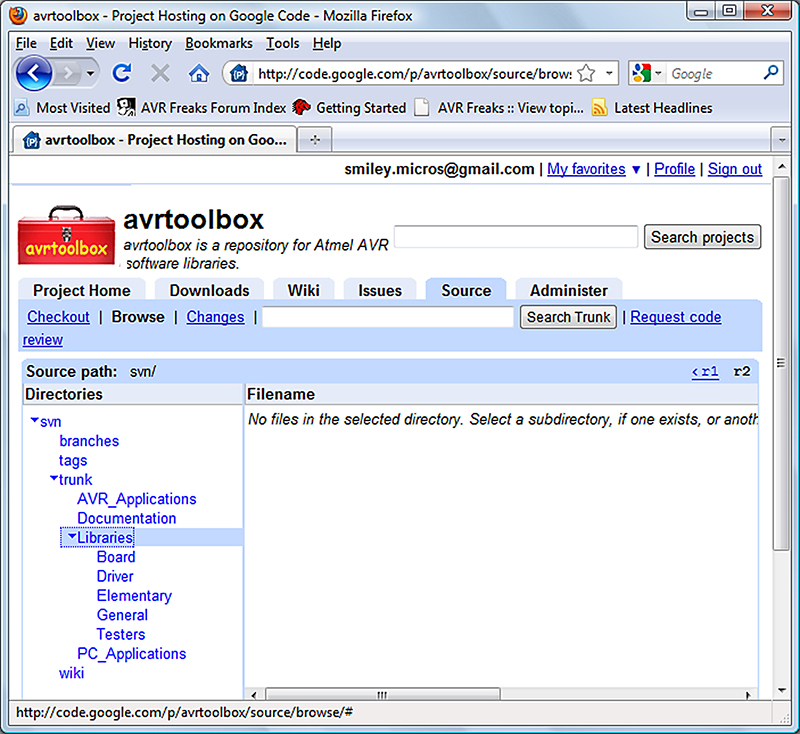

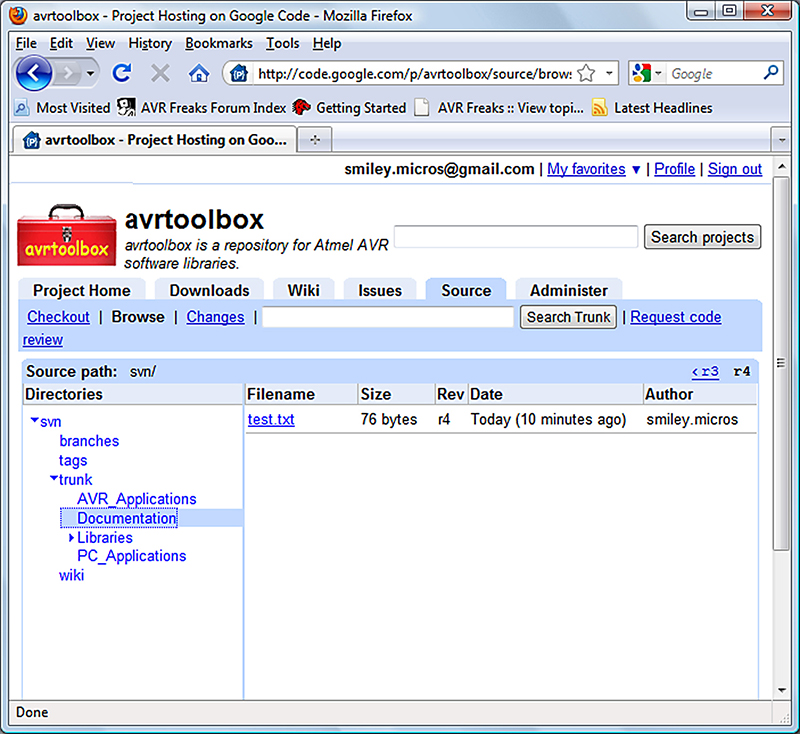

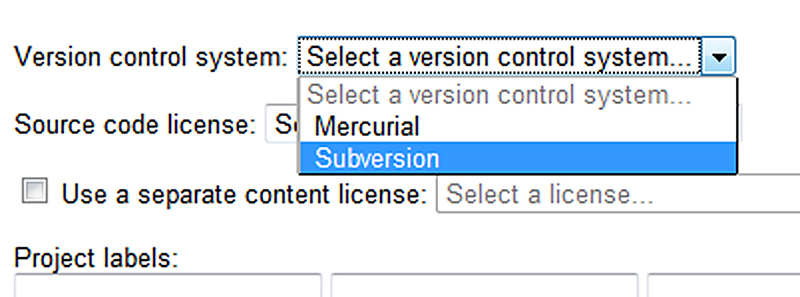

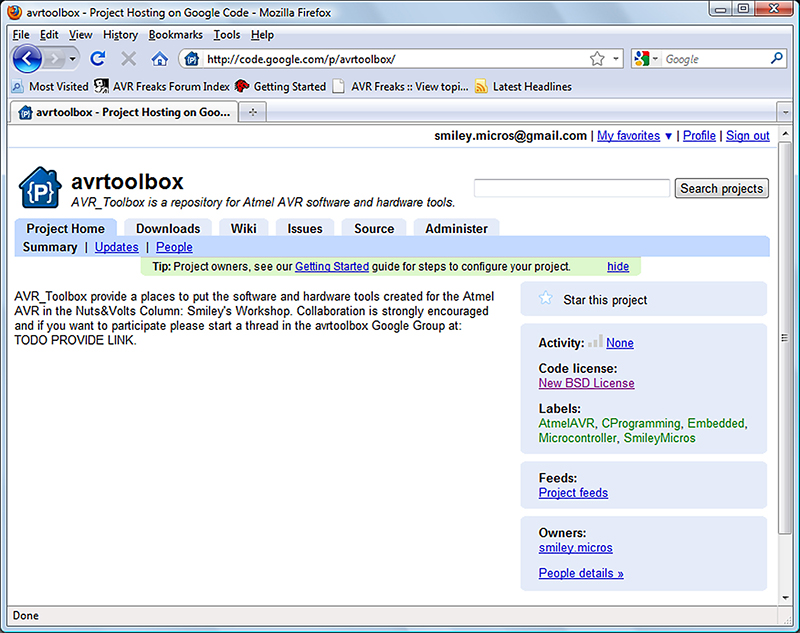

FIGURE 1. avrtoolbox Open Source Project.

This time, we're going to learn how to create an open source project using Google Code and keep track of all the different versions of the code we are writing using TortoiseSVN — both using the avrtoolbox as an example. I started off calling this series AVR_Toolbox, but since Google Code won’t accept caps I’m officially changing the name to all lowercase without the under bar. It is now simply avrtoolbox.

Open Source — The Next Big Thing?

Open source is everywhere! It’s the next big thing! Millions of people are being helped and millions of dollars are being made! Salvation is at hand! You know the story: A bunch of highly caffeinated nerdy guys get obsessed with the latest technology that is going to change the world as we know it. They search out free ‘open source’ information that tells them how to do it themselves. They borrow a friend’s shed, collect tools, and burn a lot of midnight oil hacking away at this next big thing. Soon their labors come to fruition and out rolls a world changing innovation … Linux? Arduino? Combat robots? So where today is this happening? Well folks, that’s the wrong century by two. It’s the 1890s and the nerds in question used the magazine American Machinist to get a free ‘open source’ design for an internal combustion engine. The lead hacker: Henry Ford. And out rolls his quadracycle.

From the hyperventilating Internet articles I’ve been reading lately, you’d think that open source is both new and world changing (if you believe some blogs), but it is, in fact, the next old thing being rediscovered. Nuts & Volts has been doing open source and giving it away for years, in a long tradition that goes back to Hugo Gernsback importing radio components and showing folks how to use them in the 1908 magazine Modern Electrics. So, is there any difference in what is happening today? Yes — information velocity.

In the good old days, if you had a question and if one of your friends didn’t know and you couldn’t find the answer in your pile of magazines or the library, you had to compose a letter to someone who might know the answer and wait for snail mail to get your hoped-for response. Today, you just log onto an Internet forum, ask your question, and almost instantly get a response (often RTFM or something similarly snarky). Another big difference is your circle of ‘friends’. Henry Ford was pretty much limited to his neighbors in Detroit, but with the Internet I now have friends all over the planet who can help me figure stuff out.

Another big difference is cost. This is both a blessing and a curse. The marginal cost of reproduction on the Internet is near enough to zero that it can be neglected. This magazine you are holding in your sweaty hands costs money to print, but if you get the article in an electronic format it doesn’t cost the publisher as much to send it to you. Here’s the downside: Since putting information on the Internet is so cheap that any idiot can afford to do it, many idiots do it. How do you know that something you found with Google is accurate? You don’t really.

At least with a paper magazine or book there is cost involved so somebody might have spent some time vetting the material. That doesn’t mean dead tree resources are always correct, however. I’ve made my share of paper and ink blunders, but some of the crap I’ve seen on the Internet makes me wonder if the stuff wasn’t posted intentionally to mislead. Which brings us to the worst aspect of the Internet: trolls. (Don’t get me started.)

Even with the lack of reliable filters, the Internet is still the best information sharing tool ever invented. So, I’m going to share some of the stuff I’ve been writing about by putting it in an open source project: avrtoolbox on Google Code. I put the above section on AVRfreaks for comments and, oh yes, I got some (http://tinyurl.com/393y8fc). If you aren’t familiar with tinyurl.com, it’s a free service that provides an alias for long URLs like the ones usually generated by forum posts.

Open Source Licenses Are A Sign Of Mental Illness

Open source means free, doesn’t it? Maybe, but I’ve been baffled by all the guff I’ve read about software licenses. What does “free” mean anyway? I believe nobody reads the lawyer BS, so this is what I used to put at the head of all my code: If you use this software, it will destroy whatever machine you use it on and kill anyone in a one kilometer radius. So, don’t even consider using it for any reason whatsoever! Have a nice day.

I thought that by not having a license, the code was free to use, and that by joking about destruction no sane person would think to sue me if the code wasn’t perfect. Then, someone informed me that by not having a license on my source code I was actually copyrighting my code and other folks couldn’t legally use it. Apparently, the restrictive copyright comes with the creation, so you have to explicitly reject the standard copyright and use a license to let other folks use your materials. So, I read a bit about licenses and found some of the most esoteric philosobabble discussions by people who truly have too much time on their hands. After hours of reading about what ‘free’ really means, I decided these guys are freaking crazy. I couldn’t pick a license. Thankfully, I stumbled across Google Code which says this: “The open source community has been flooded with lots of nearly identical licenses. We’d like to see projects standardize on the most popular, time-tested ones. The selected licenses offer diversity to meet most developer needs.” Then, instead of allowing hundreds of choices, they only allow nine [only?]. I selected the ‘New BSD License’ because someone I trust who is nominally sane said it was the least restrictive.

I posted this section on AVRFreaks and started a thread that turned immediately into an ‘esoteric philosobabble’ discussion (http://tinyurl.com/27s3y37).

Collaborative Open Projects

Then there is the silliness of open source hardware. Excuse me, but ‘source’ refers to ‘source code.’ The open hardware folks get into discussions of source that rival those on the meaning of free. So, I’m going to settle this for me by using COP — Collaborative Open Projects — to refer to anything where folks collaborate on a project and intend the documentation to be free (as in no money and no lawyers). Like everything else Internet, there are a buzzillion ways to have a COP. I’ve chosen Google Code which may not be the best but it seems the simplest to me, and I need simple.

Google Code

There are some great free software development tools available on the Internet. In fact, some is an under-statement. There are so darn many tools that (like licenses) it is nearly impossible to decide what is best for any particular purpose. I decided that I wanted to collaborate with folks on open source projects, but I didn’t have much of a clue where to start. I spent a few days digging around and finally decided that I wouldn’t be able to declare any ‘best’ way to do this. So, without saying that I’ve found the best free solution, I will say I’ve found a good set of tools and am beginning to learn how to use them.

Remote Open Source Code Repository

As I’ve stated, I chose Google Code. Why didn’t I choose SourceForge or github or some other website? Mainly because the Google Code site looks simple and clean. Also, after reading some stuff on the Google Code website, I saw that they are restricting choices to the most commonly used sorts of things. Now one might be opposed to having restricted choice (freedom and all that), but when you’re learning, a little guided restriction can be a blessing. I have to trust that Google is being reasonable in winnowing the choices consistent with the goals.

The first objection I’m going to hear about from you is that Google Code requires you to register. So, this doesn’t mean they are going to steal all your personal information and send it to that son of a recently deceased government official in Nigeria who wants you to help him transfer $12 million to the US. Enough making fun already – just sign up with Google or go away and do your own thing.

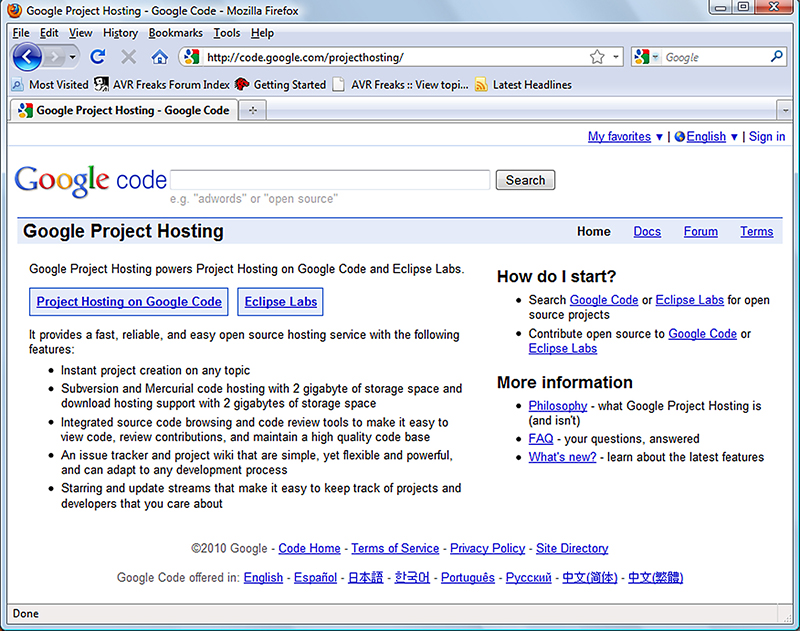

Google Code Create Project Recipe

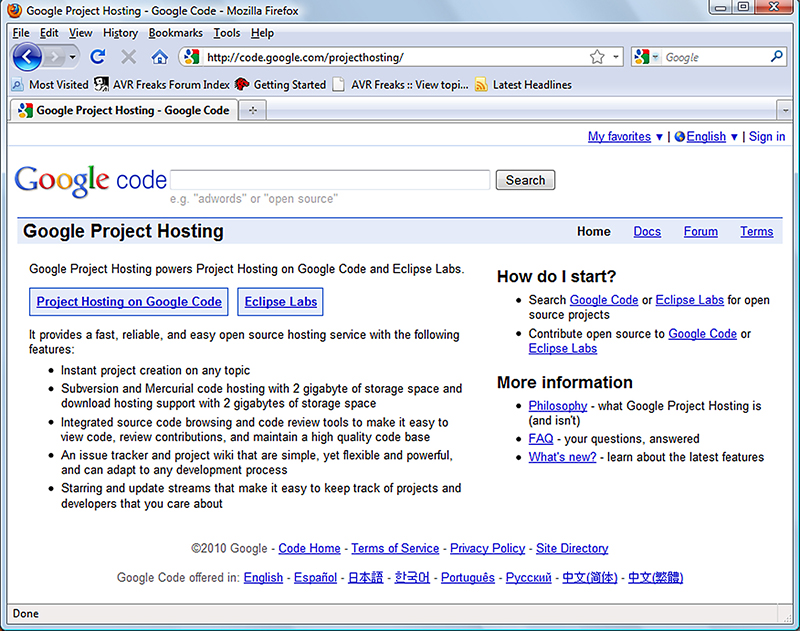

I presume you’ll create your own project and put it under version control to learn these skills. I recommend patience since I did this three times and had some difficulties each time (including losing my freaking password). Let’s learn how to start an open source project and do it cookbook style. Go to http://code.google.com/projecthosting/. Click ‘Project Hosting on Google Code’ shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. Google Code Project Hosting.

- Click ‘Sign in to create a project.’

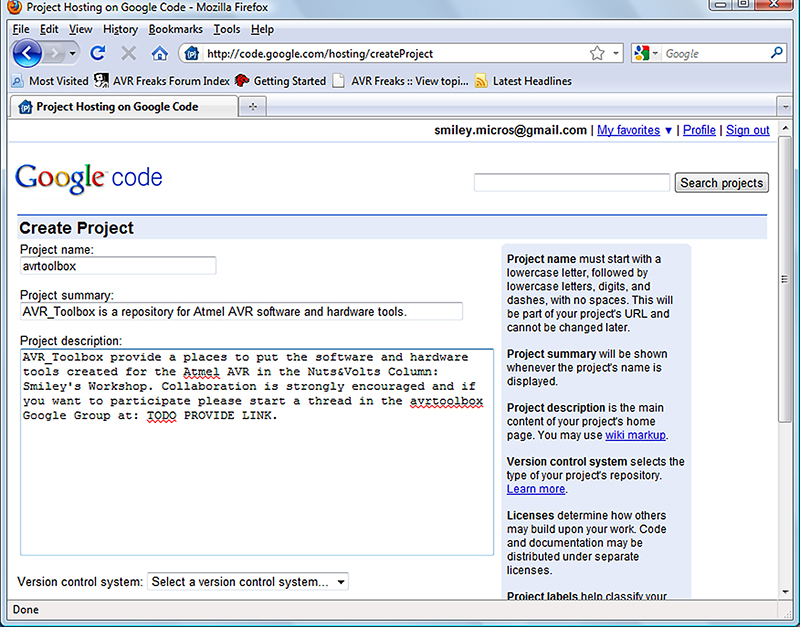

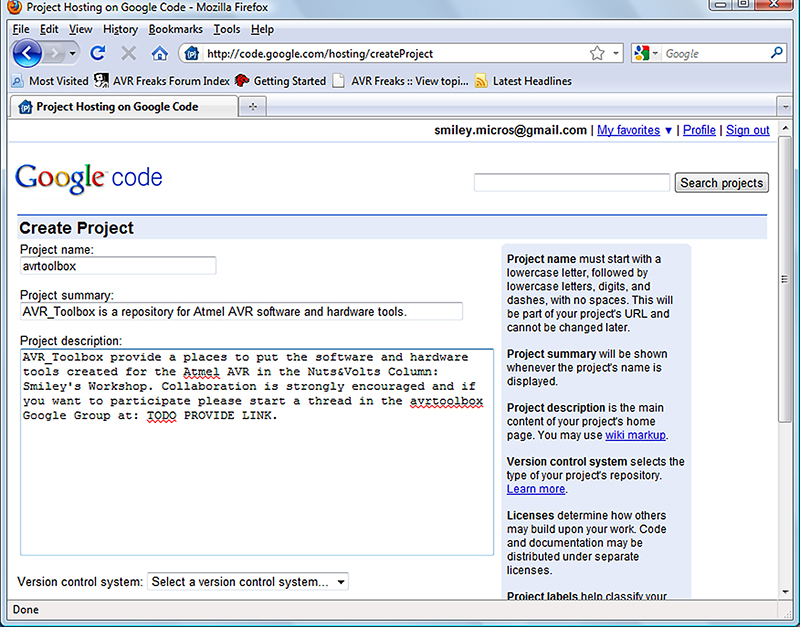

- Click ‘Create a new project’ and fill in the project information as shown in Figure 3. Note that the project name must be all lowercase and cannot have certain characters. For example, it wouldn’t take Avr_Toolbox but did take avrtoolbox. (Possibly somebody at Google forgot what century we’re in?)

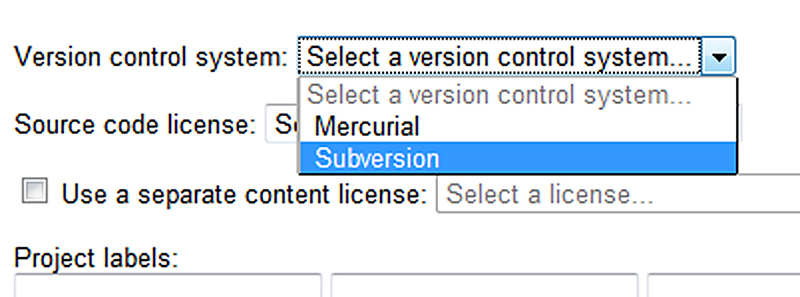

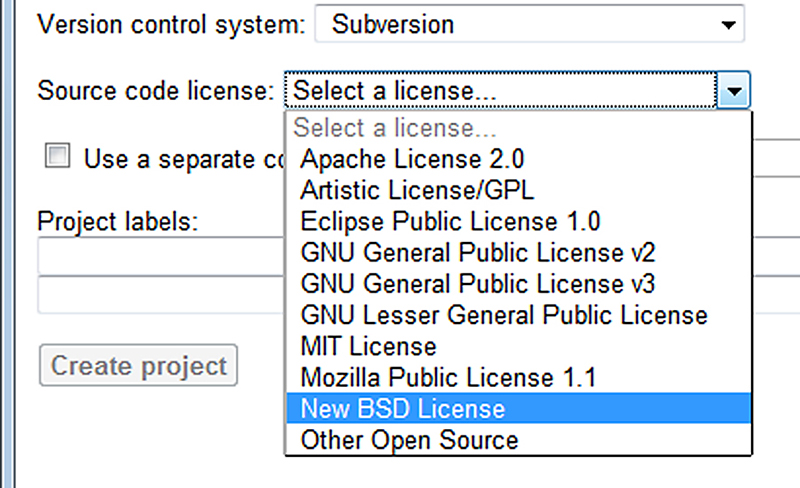

- Click on ‘Version control system:’ as in Figure 4.

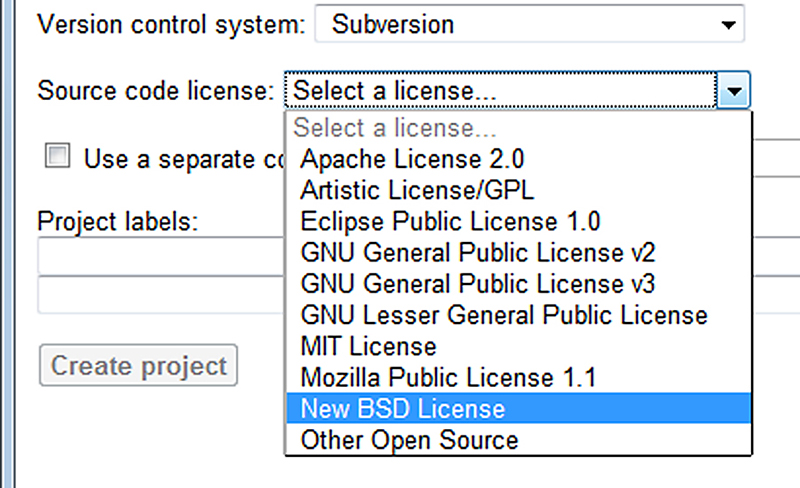

- Click on ‘Source code license:’ as in Figure 5.

FIGURE 3. Google Code Create Project.

FIGURE 4. Google Code Select Version Control System.

FIGURE 5. Google Code Select License.

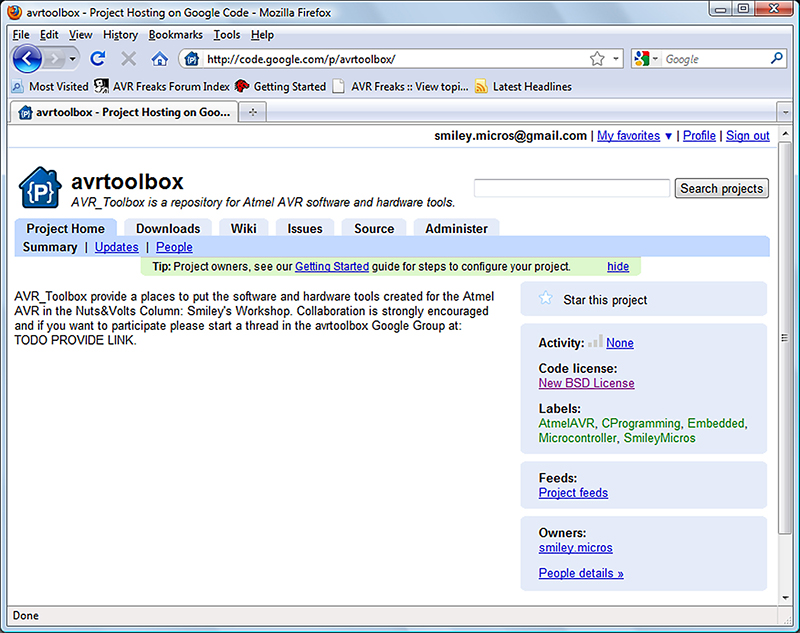

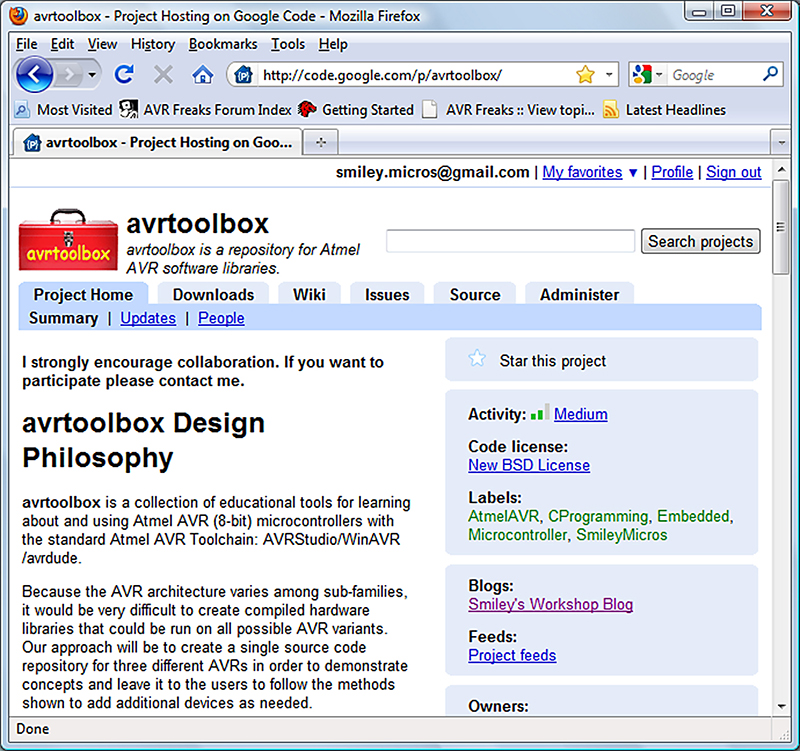

FIGURE 6. Google Code avrtoolbox Project.

So, now we have Figure 6.

Version Control — It’s A Time Machine

A version control system manages files and directories, and the changes made to them over time. It allows you to recover your older work and track the history of the changes you’ve made. When you smack your head over something really stupid you’ve been doing for a few days, you’ll be glad you have a version control system time machine to take you back to your last intelligent moment so you can examine the details of when you messed up. If you are like me, you’ll just revert to that moment and trash the rest. However, with a version control system, you don’t actually trash anything so if you decide that your stupid period maybe wasn’t so stupid after all, you can recover those bits.

Another really useful feature is that a version control system allows several folks to work on the same stuff at the same time without risking destroying each other’s work. If you and I check out the same thing and each make a change, the system will tell us to have a discussion about it before it will let either of us put it into the system.

If you’ve never used a version control system before, you’ll need to learn some of the lingo so that you can talk the talk. To save space, I’ll recommend that you mark this spot and then proceed to the Internet book: Version Control with Subversion, Chapter 1. Fundamental Concepts (http://svnbook.red-bean.com/en/1.5/svn.basic.html). They do a great job so there’s no reason to repeat it here. I do suggest you mark this spot when you finish that chapter since the rest of the book can get a bit hairy without a guide. Let’s set up a real version control system for our avrtoolbox project.

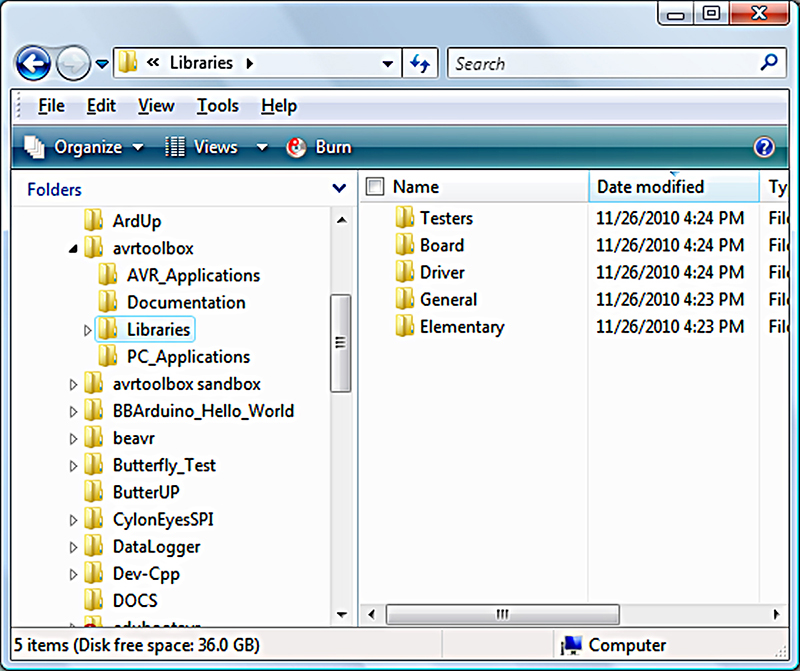

TortoiseSVN And Our Project Directories

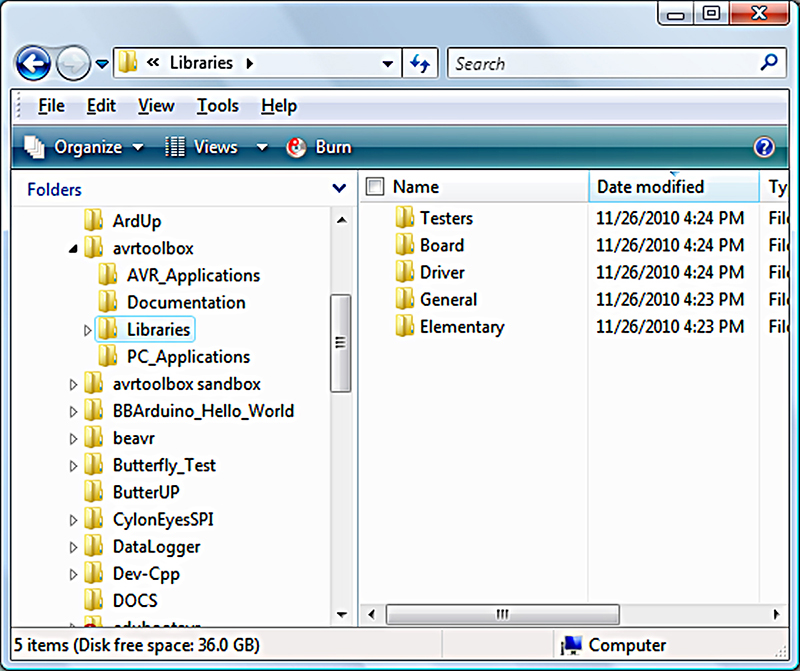

You can get your free copy of TortiseSVN at http://tortoisesvn.tigris.org/. Follow their instructions to get it installed on your PC. Let’s start by creating a directory tree so we’ll have something to put under version control. I decided on (see Figure 7):

FIGURE 7. avrtoolbox in Windows Explorer.

- avrtoolbox

- AVR_Applications

- Documentation

- Libraries

- Elementary

- General

- Drivers

- Board

- Testers

- PC_Applications

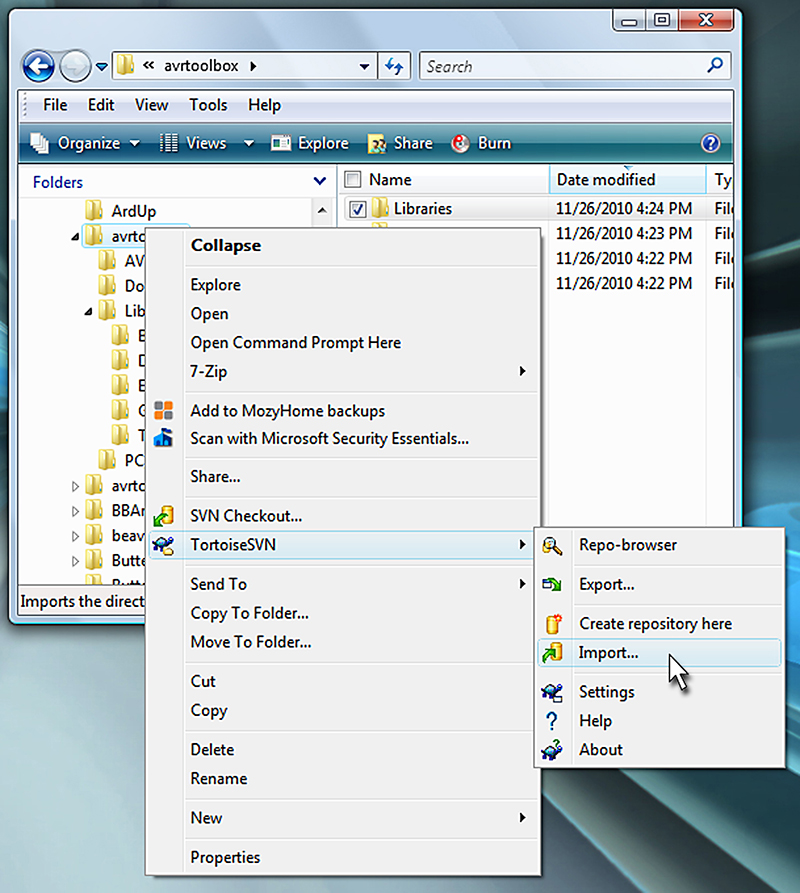

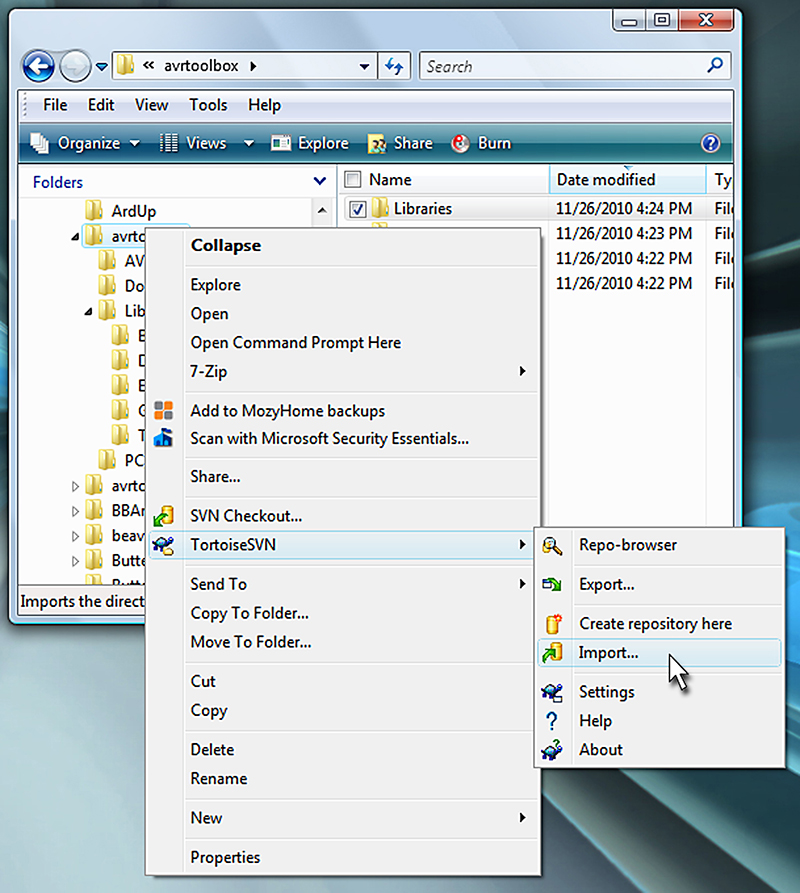

Make sure you are attached to the Internet, then right-click on the avrtoolbox directory and select the TortoiseSVN import as shown in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8. Right-click avrtoolbox and Select TortoiseSVN Import.

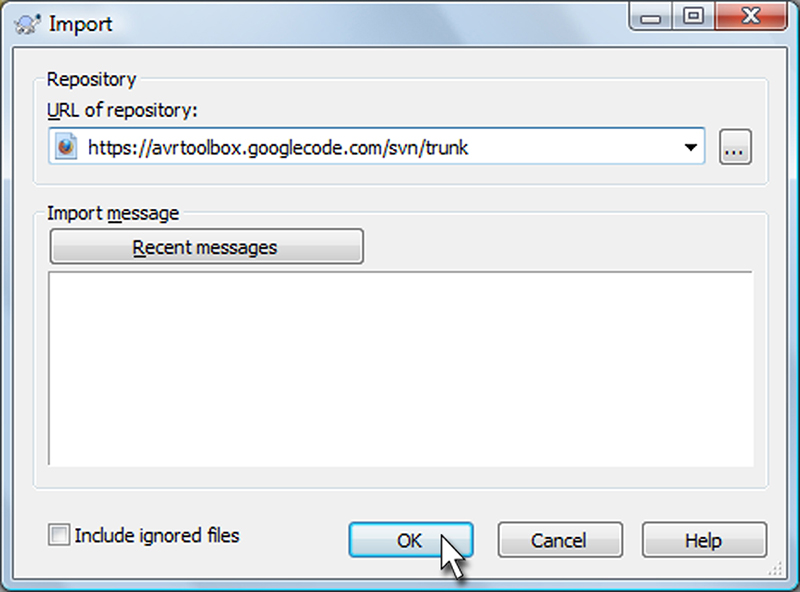

This is very non-intuitive since what you are really doing is uploading the directory tree to your Google Code project; from the perspective of that project, you are ‘importing’ those directories from a PC out in space somewhere. You are at your PC but your repository is at Google somewhere. That’s the perspective taken by TortoiseSVN. This will open the window shown in Figure 9.

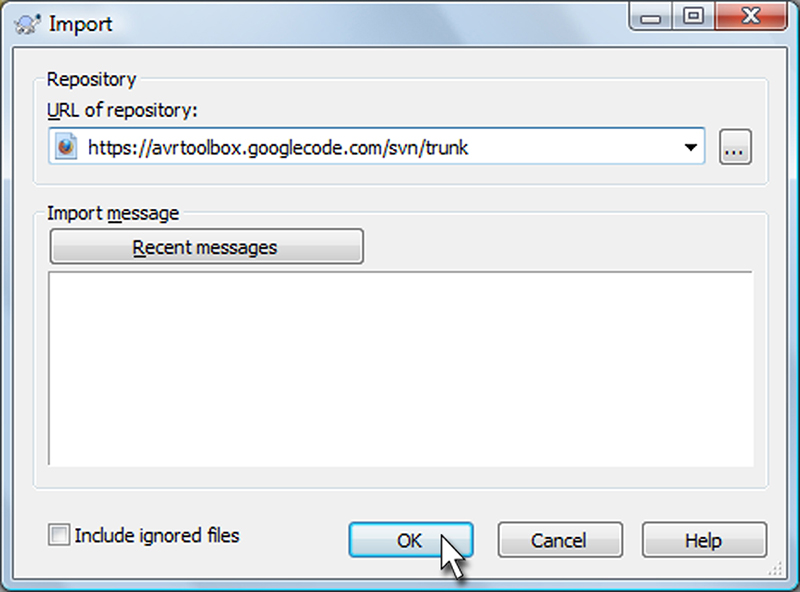

FIGURE 9. Import to Repository.

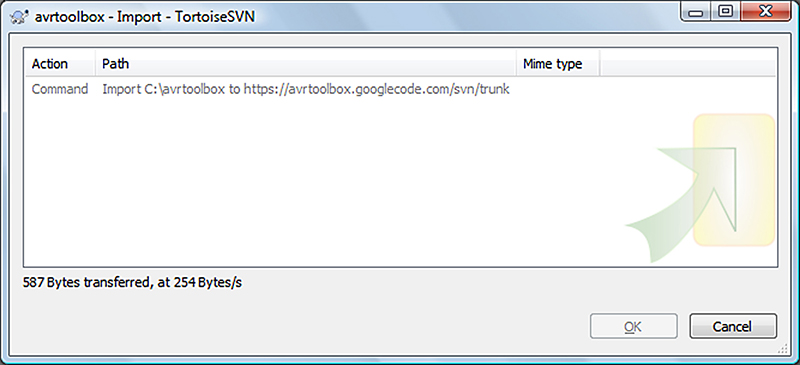

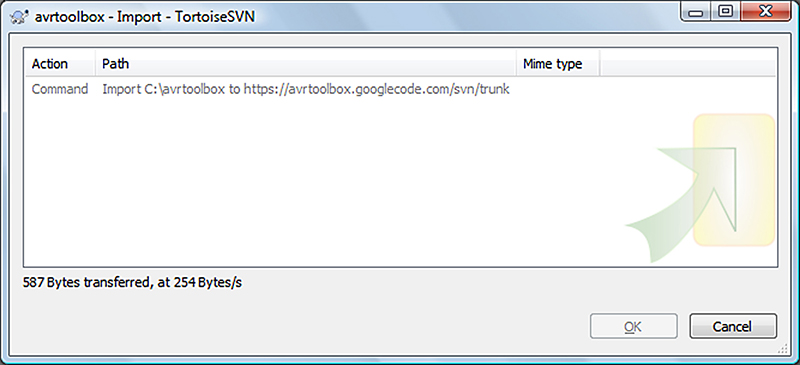

Click OK and you’ll see the window in Figure 10.

FIGURE 10. TortoiseSVN Import.

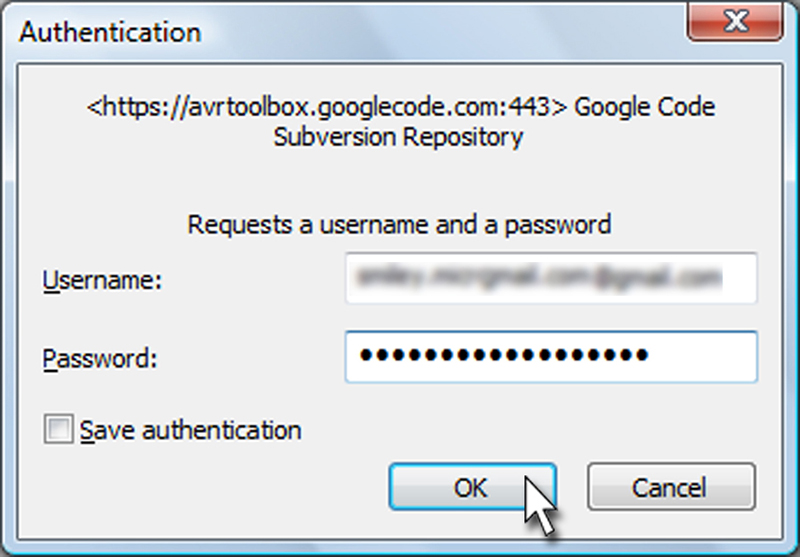

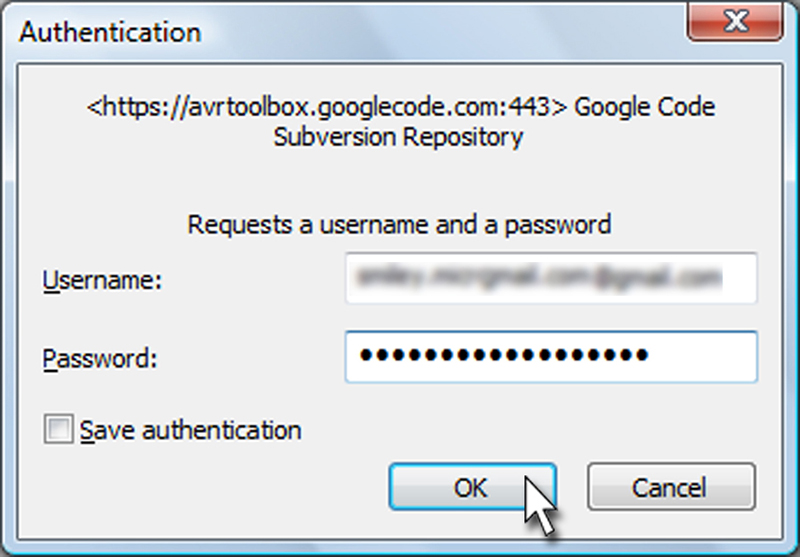

Next, you’ll see the Authentication window shown in Figure 11.

FIGURE 11. TortoiseSVN Authentication.

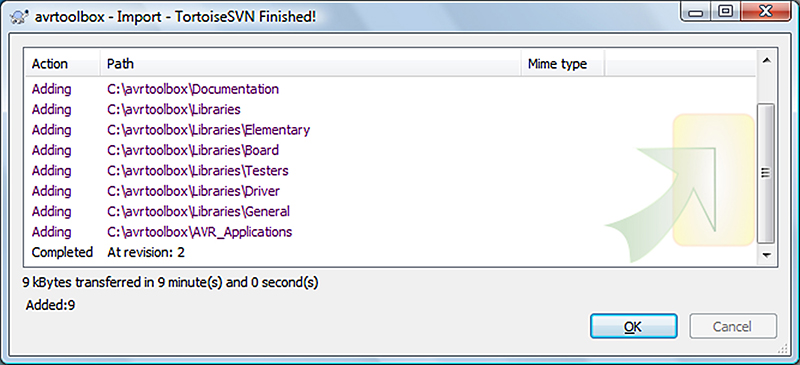

Be sure and remember that the password requested is specific to the Google Code project you created and is NOT the same as your general Google password. This bit me a few times. Click OK and you’ll see Figure 12.

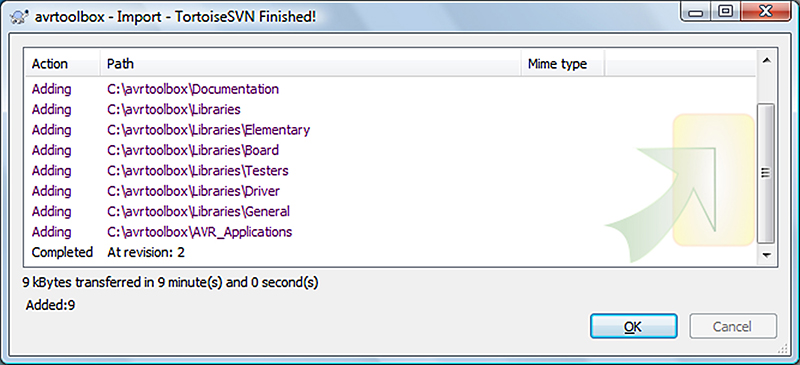

FIGURE 12. TortoiseSVN Finished Importing.

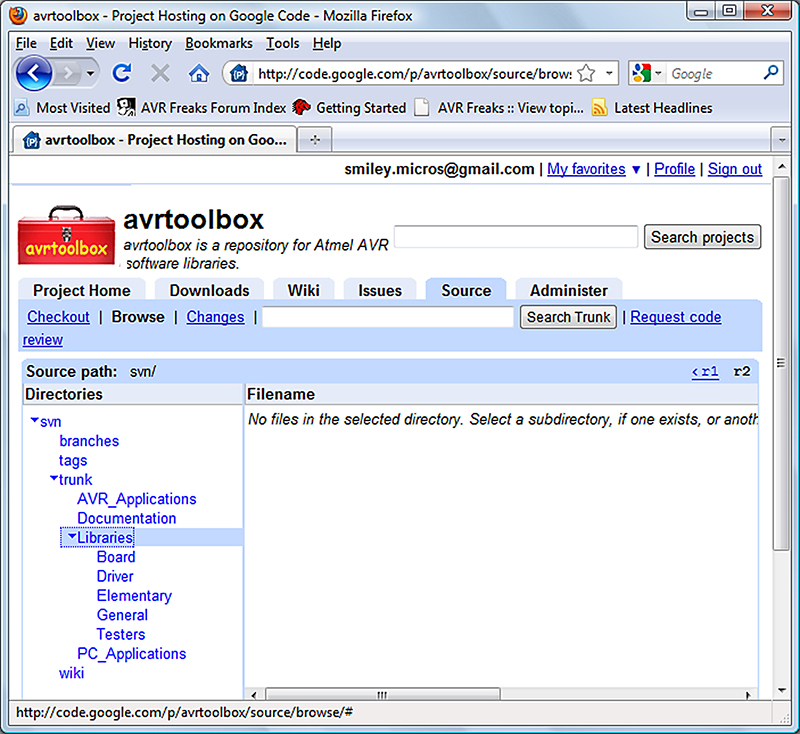

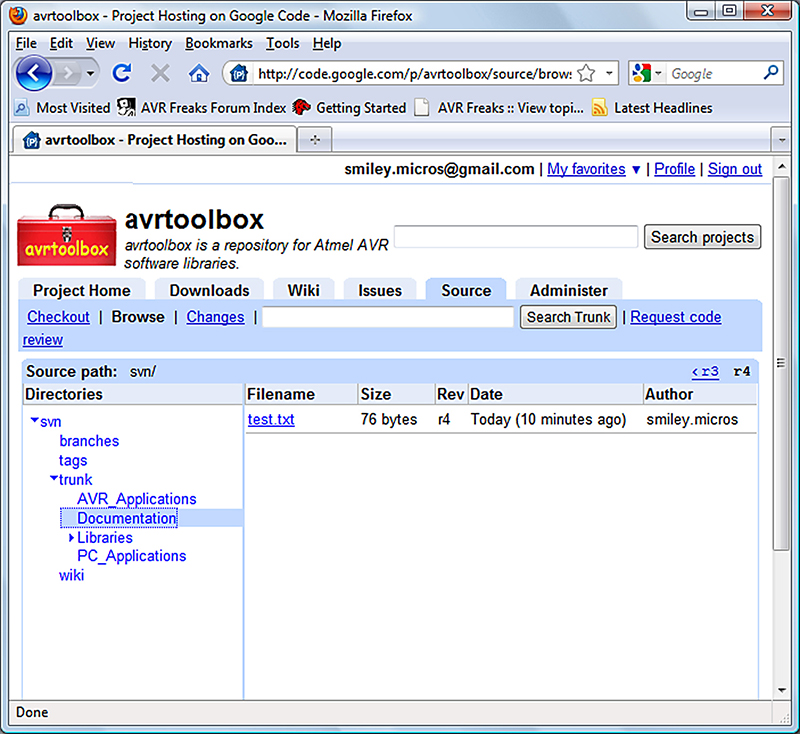

Now, go to the avrtoolbox project on Google Code and click on the Source tab and the Browse button; you’ll see Figure 13 which verifies that you’ve successfully imported the directories.

FIGURE 13. Google Code SVN Directory Tree.

Example Of Version Control

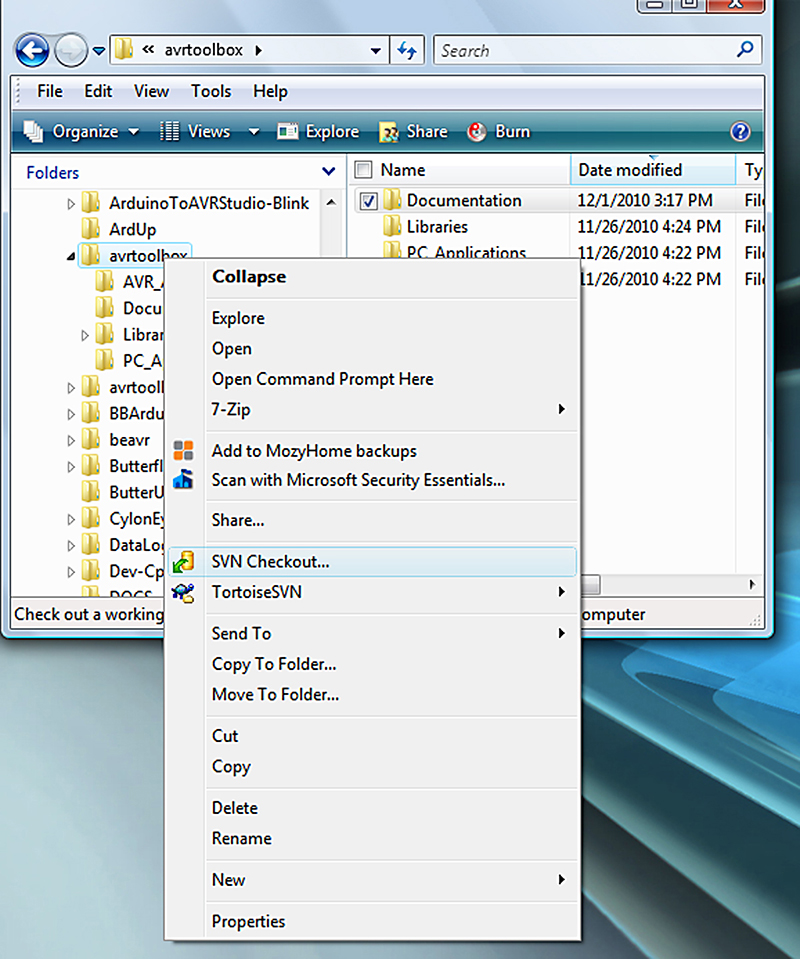

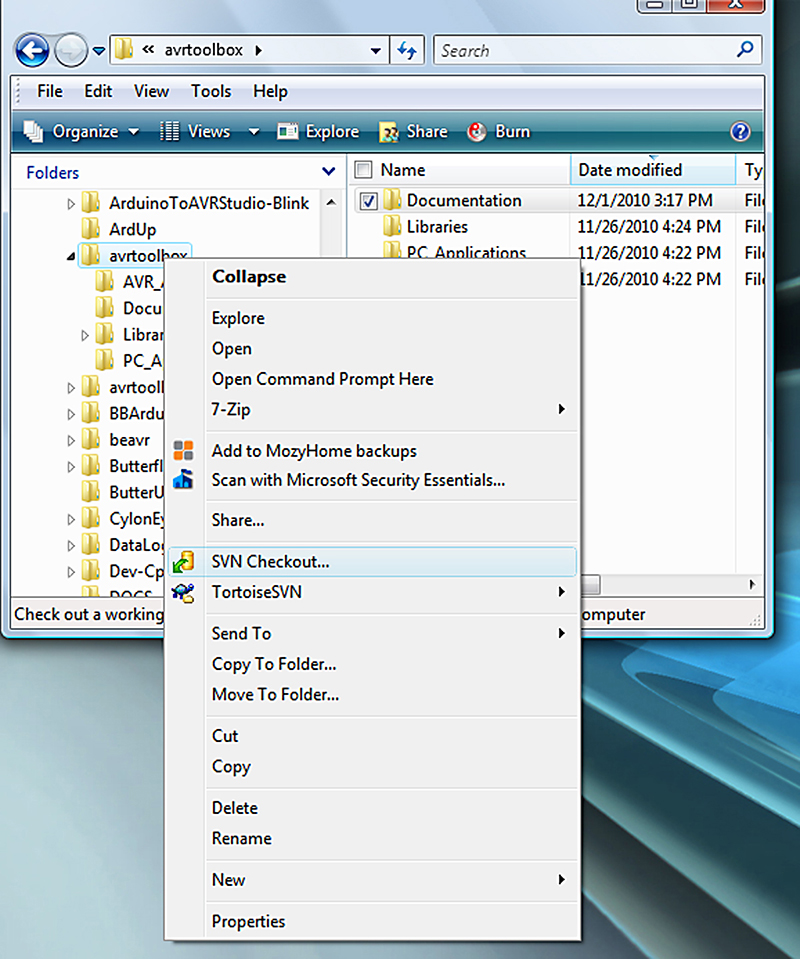

After we get the directories on our Google Code project, we need to link them back to the directories we have on our PC. Right-click on the avrtoolbox directory in Windows Explorer and then click on SVN Checkout as shown in Figure 14.

FIGURE 14. SVN Checkout.

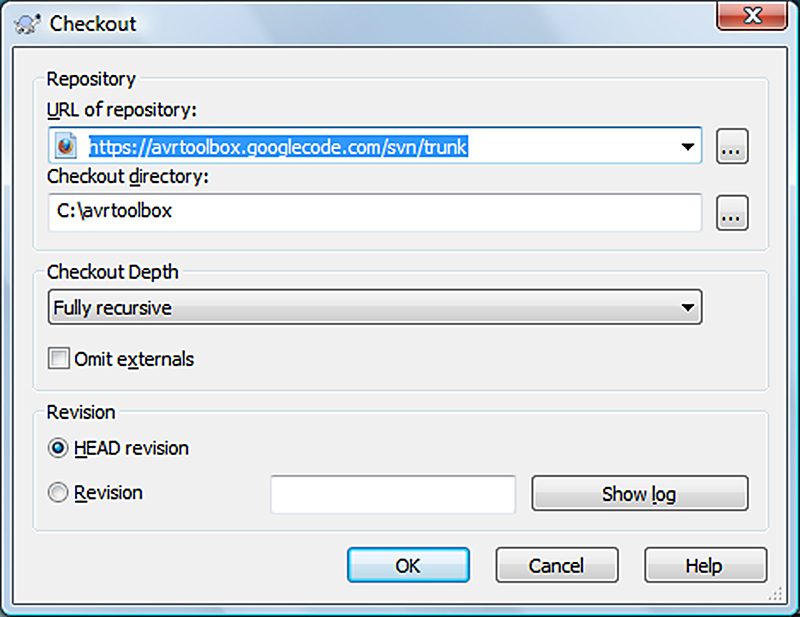

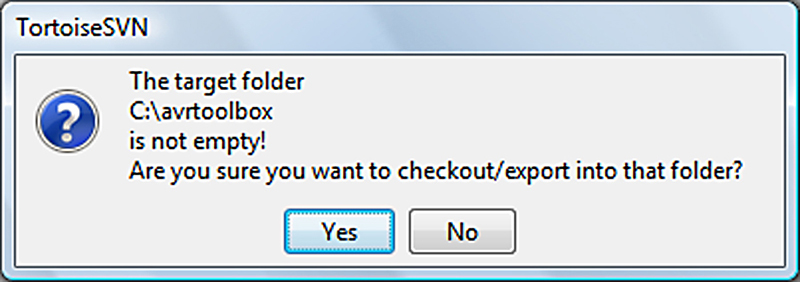

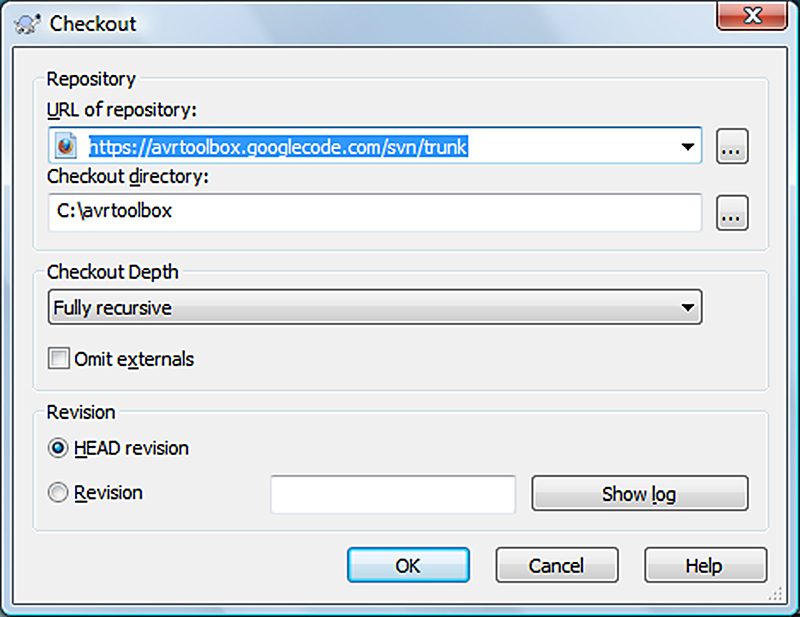

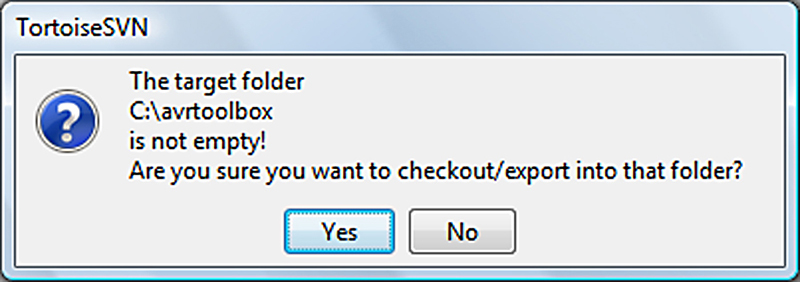

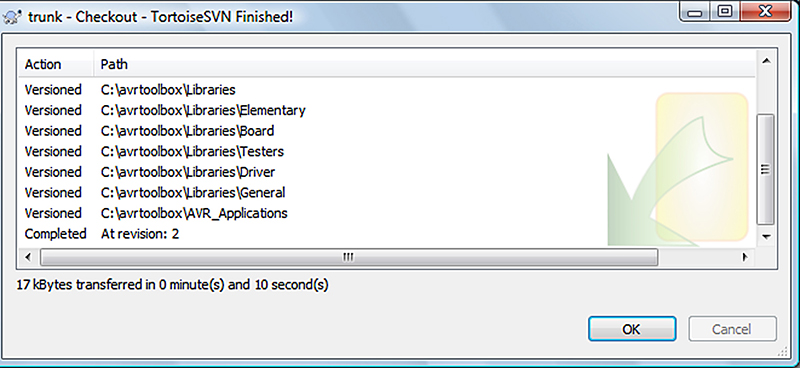

Figures 15, 16, and 17 show the process for completing the Checkout.

FIGURE 15. TortoiseSVN Checkout.

FIGURE 16. Are you sure? Duh, yeah!

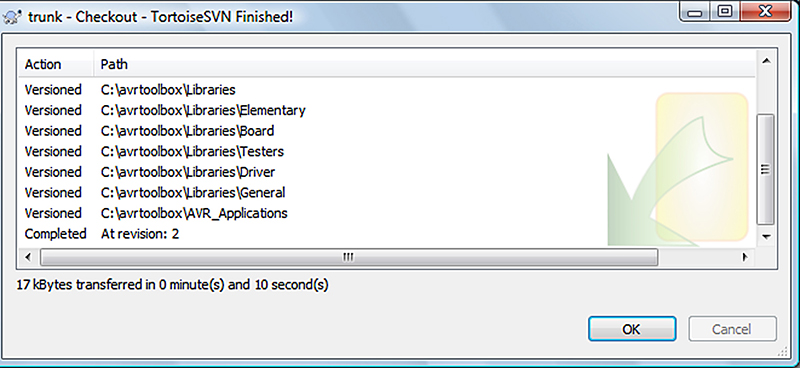

FIGURE 17. TortoiseSVN Finished.

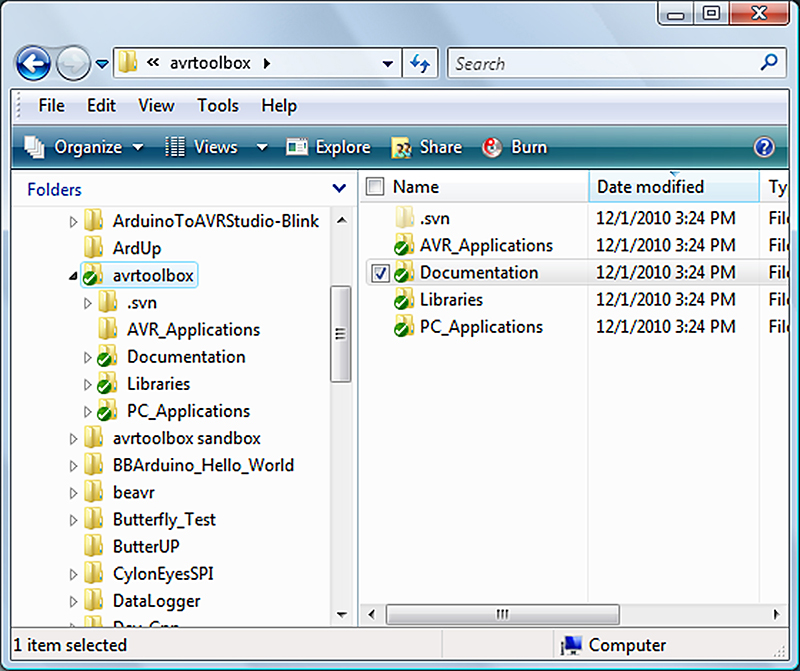

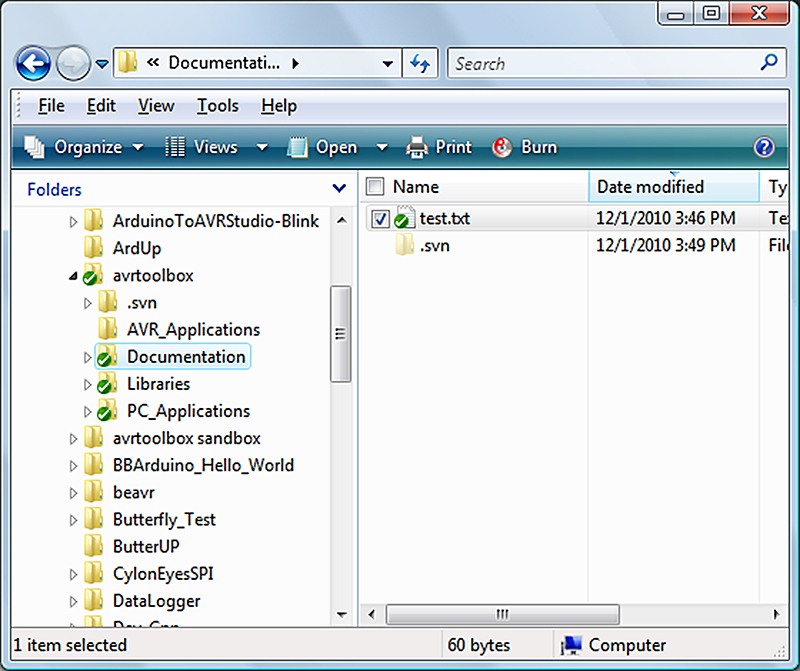

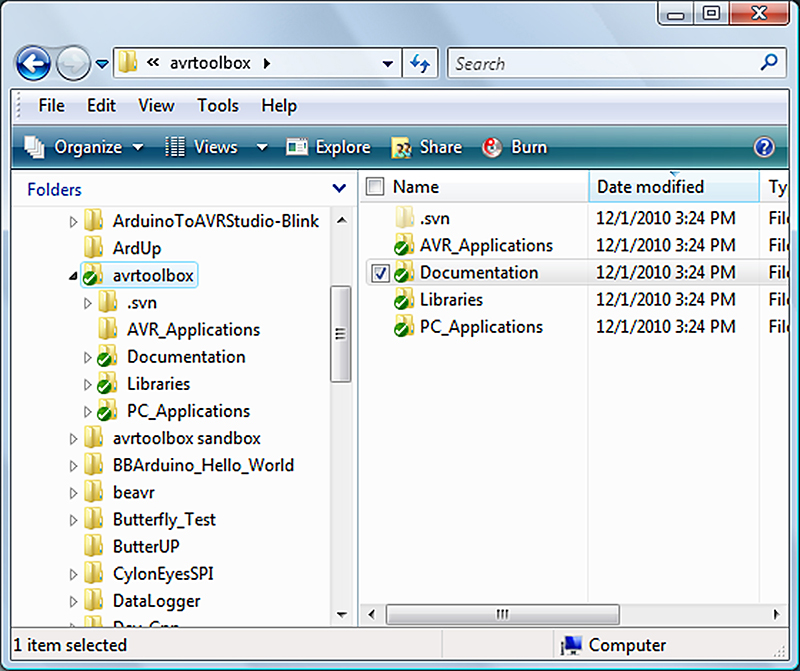

Now that you’ve got them checked out, TortoiseSVN puts a special green checkmark on the directories in Windows Explorer as in Figure 18.

FIGURE 18. TortoiseSVN Checkout Successful.

Test It With A Text File

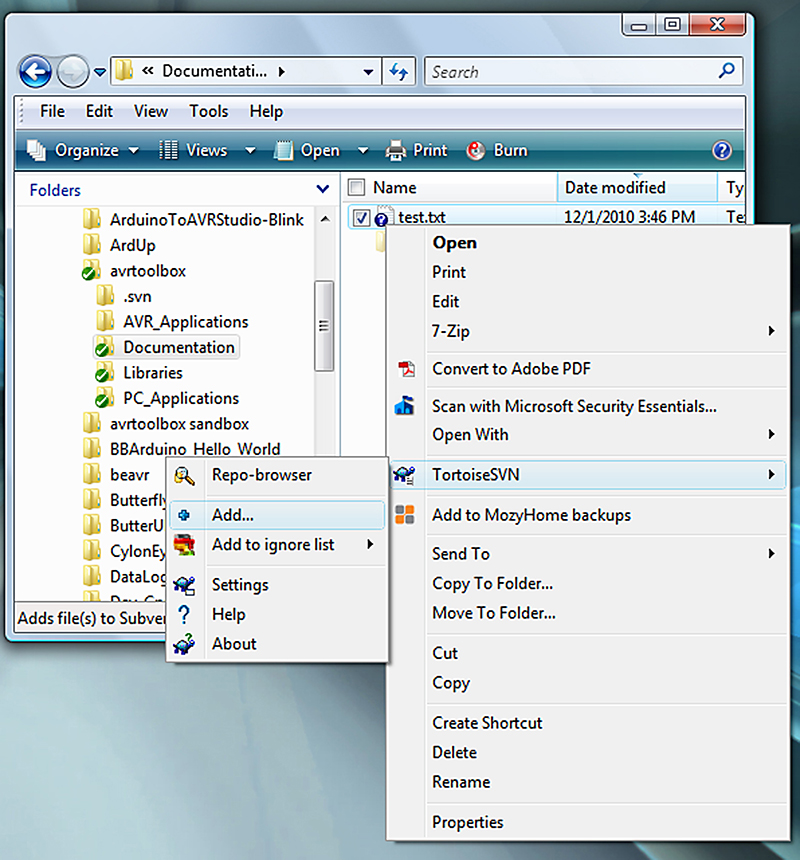

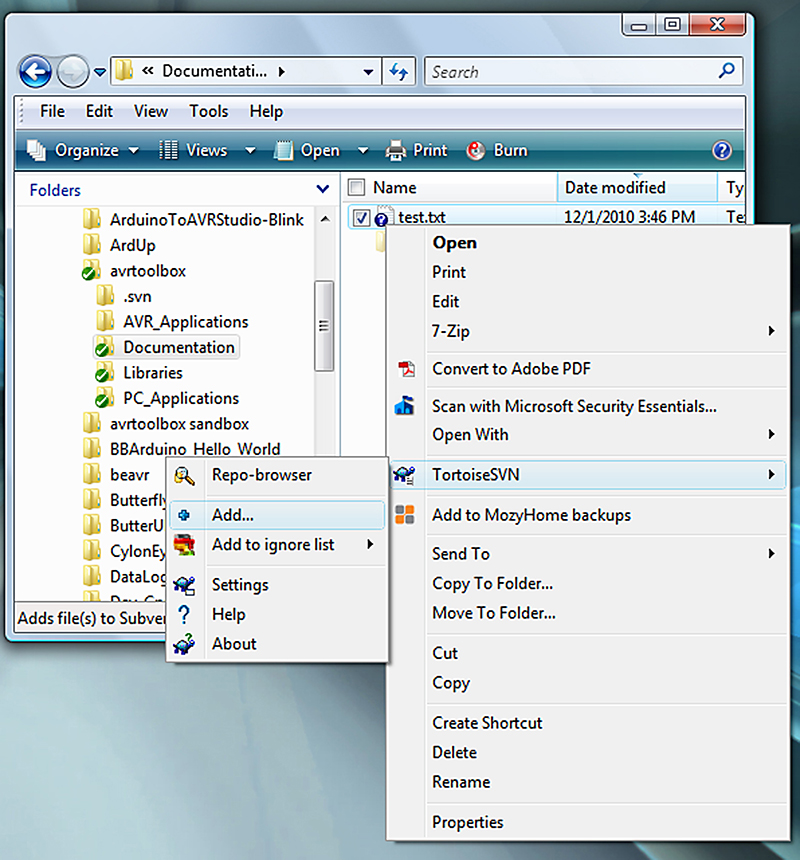

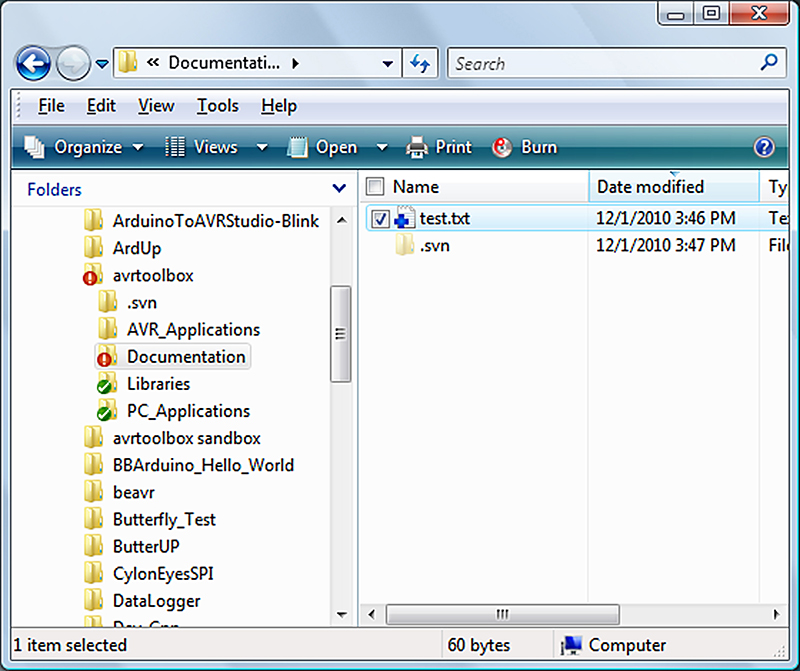

That was great, but now you have a bunch of empty directories. Let’s put a text file in one so that we can see how our repository on the Internet cooperates with the directories we have on our PC. Let’s create a simple test file in the Documentation directory: test.txt with the single line: ‘This is a test of avrtoolbox.’ We right-click on the file and then select Add ... as shown in Figure 19.

FIGURE 19. TortoiseSVN Add a File.

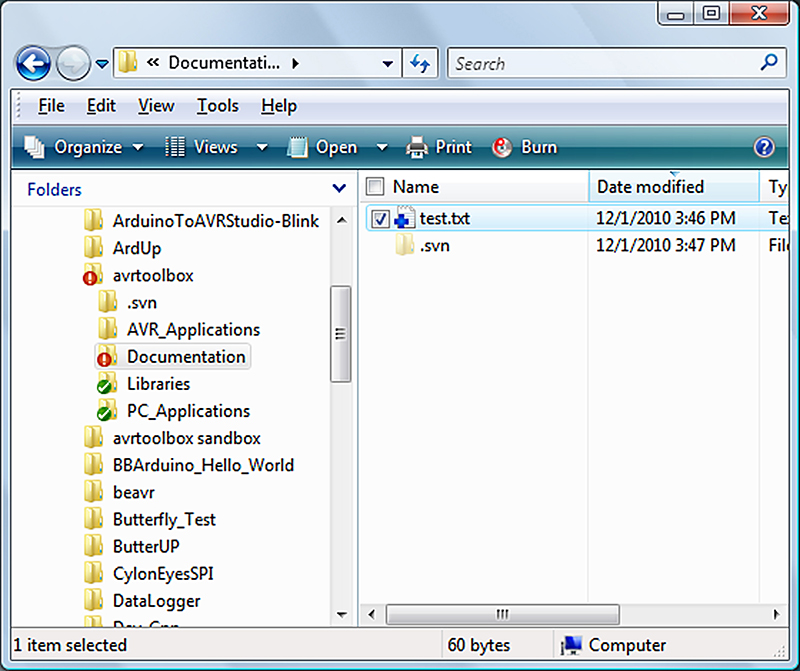

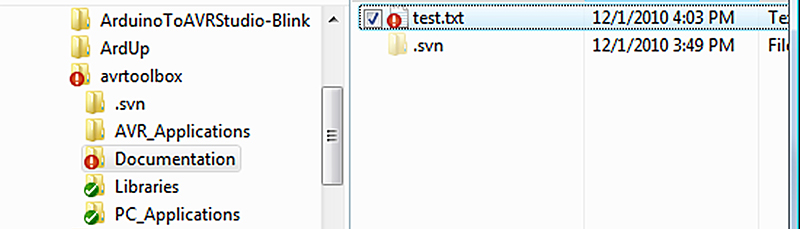

Now we see that the folder icons have changed as shown in Figure 20.

FIGURE 20. Directory Tree After File Added.

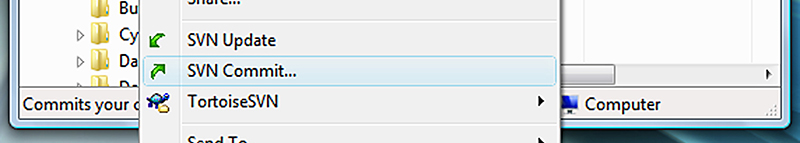

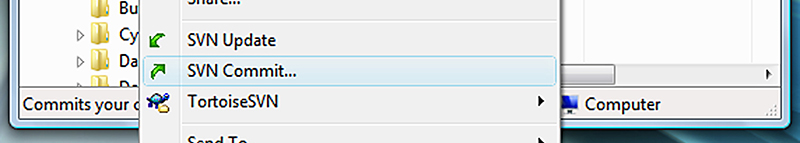

The avrtoolbox and the Documentation directories have a red dot exclamation mark on them indicating that they are no longer in sync with the repository. To get them in sync, we right-click on the avrtoolbox directory and select SVN Commit as shown in Figure 21.

FIGURE 21. TortoiseSVN Select SVN Commit.

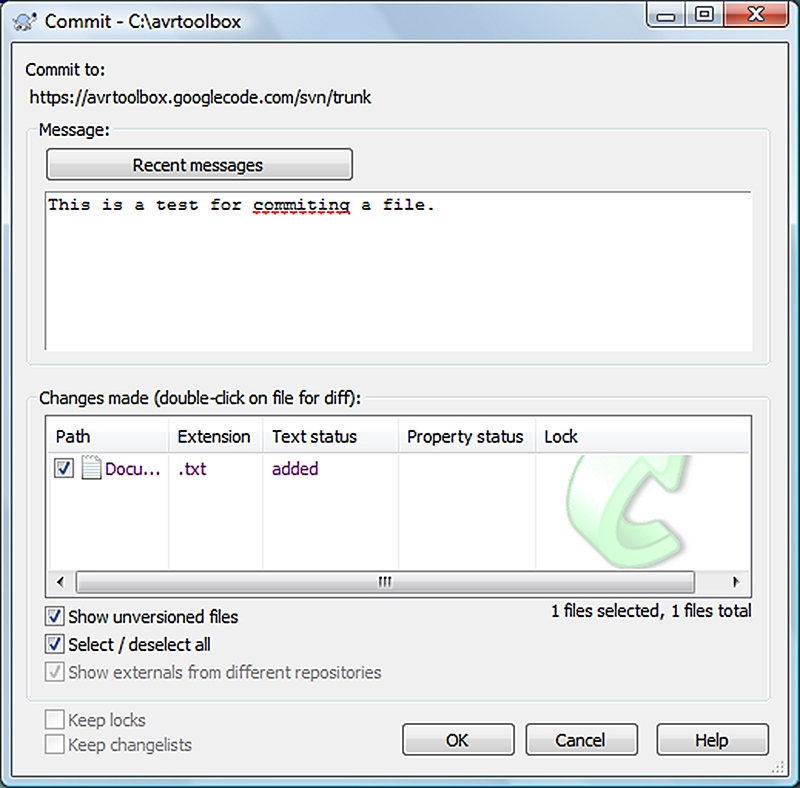

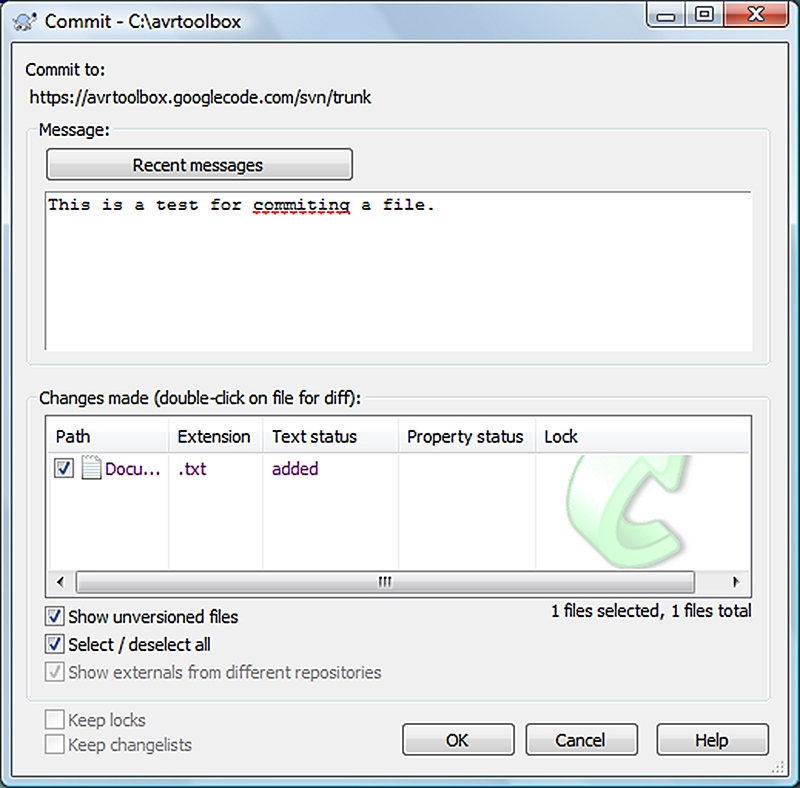

This brings up a familiar window to which we add a comment about our file as shown in Figure 22 (with spelling error!).

FIGURE 22. Tortoise SVN Commit (with spelling error!).

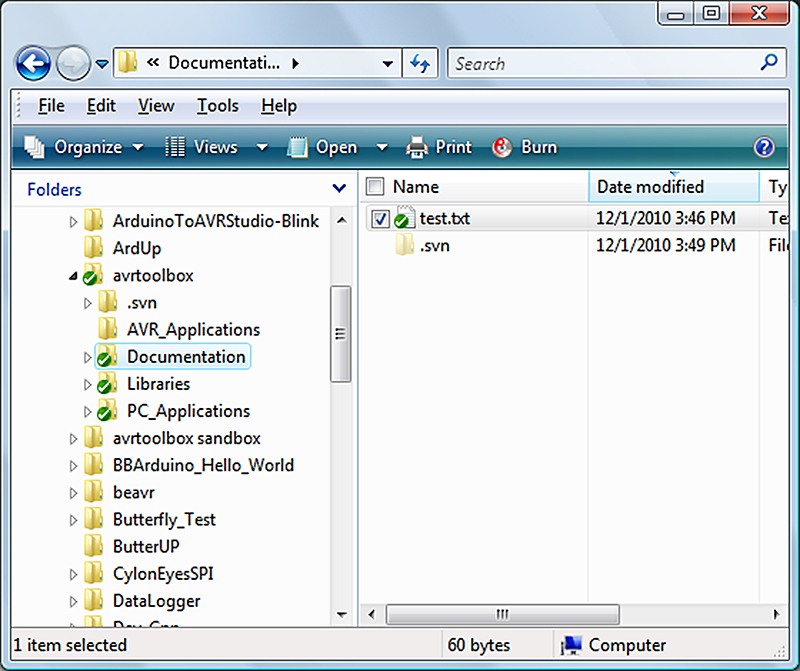

This syncs the PC and the repository so we get Figure 23.

FIGURE 23. Greenlights all the way!

What Happens If We Change The File?

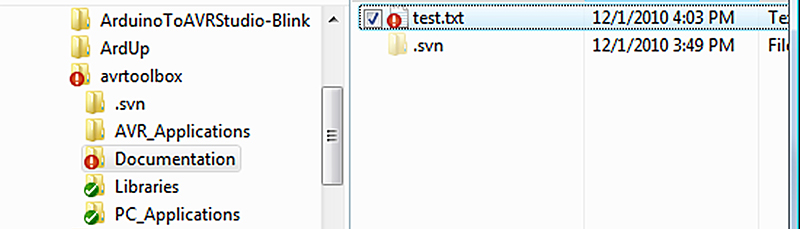

Let’s add a sentence to our test.txt file: ‘This line added to generate a changed file.’ We get the red icons as in Figure 24. Only this time, one is added to the test.txt file.

FIGURE 24. TortoiseSVN Test File Changed.

So, we repeat the stuff we did earlier. We right-click on test.txt, select TortoiseSVN Commit, and click our way through the process including signing in again, etc., to commit the newest version and change the icon backto green.

So, What Do We Have Now In Google Code?

Let’s look in our project directories in Figure 25. Now it’s time to play with this a bit.

FIGURE 25. Google Code Test File in Directories.

Go to the Google Code project and click on things and see what happens. For instance, click on the test.txt file and you’ll see not only the text in the file but the revision history.

This was a lot for one article. I’ll be writing about many new AVR tools and putting the source code in our open source project. My hope is that some energetic folks will join in and help make this a really useful tool for the AVR community.

Let’s Not Forget

The first thing you are going to forget is that the Google Code repository sign-in requires a different password than your Google account. Also, you will create directory paths with spaces or weird characters that avrdude won’t take, so don’t do that either.

Next time, we’re going to bring all these organizing principles together and use them for a serial library. If you just can’t wait and want to get a good leg up on C and the AVR while helping support your favorite magazine and technical writer, then buy my C Programming book and Butterfly projects kit from the Nuts & Volts website. NV