The Story of a Secret Weapon Called “Aspidistra”

Among the best-kept secrets in Great Britain during World War II was a 600 kW medium-wave transmitter which was codenamed “Aspidistra.” The transmitter would disrupt the German war machine through misdirection and fake news.

The origins of Aspidistra go back to 1932, when Powel Crosley, Jr. — an American radio manufacturer and broadcaster — conceived of a superpower transmitter. It would broadcast at 500,000 watts — ten times the power of any other station in the United States. RCA was the designer and primary contractor, with help on various elements from Westinghouse (controls) and General Electric (RF). The cost was an estimated $400,000.

Crosley put his 500 kW transmitter on the air on May 1, 1934. With coverage of half of the US at night, Crosley was able to get network-level advertising rates ($1,200 per minute). There immediately arose a hue and cry from one end of the country to the other as competitors demanded to be allowed to broadcast at 500 kW.

Several applied for high-power licenses. In 1937, WJZ in New Jersey (today WABC) jumped ahead of the pack and commissioned RCA to build a “twin” of the WLW transmitter. RCA decided that the future for high power was rosy and went to work.

Unfortunately, in 1939 (about the time the WJZ transmitter was completed), the high-power party came to an end. The Federal Communications Commission refused to renew WLW’s license to use 500 kW. The decision was probably a political one. To seal the fate of the big transmitter, Congress enacted a law that made 50 kW the absolute maximum for commercial broadcast power. It remains in force today.

WLW did use the full 500 kW after the US entered WWII, but that is another tale.

So, it was that RCA found itself stuck with a “white elephant” that it could not sell — not in the US at least. So, the ultra-high-power transmitter sat unused in RCA’s Camden, NJ factory for the next two years. The Chinese government had taken an option to buy the transmitter but had yet to exercise it.

In Great Britain, engineers had been discussing the potential uses of a superpower radio transmitter since 1938, when the government set up secret departments to prepare for sabotage, subversion, propaganda, and other forms of irregular warfare.

In 1941, Colonel Richard Gambier-Perry, who headed radio communications for the British SIS (better-known as MI6), learned of the 500 kW transmitter. He traveled to the US in May to inspect the equipment and secured an option for Britain to buy it.

Gambier-Perry advised his superiors that the RCA transmitter could be a “raiding dreadnought of the ether” in the radio propaganda aspect of the war with Germany. Its super power could fire broadcasts into Europe and beyond. Prime Minster Churchill signed off on the project immediately. To him, it was another big gun.

RCA’s price for the transmitter was £111,800 and change. That amount was the equivalent of what Crosley paid for WLW’s transmitter in 1934, so RCA didn’t suffer in the deal. Spare parts and site preparation kicked up Britain’s estimated overall cost to £165,000.

During the summer of 1941, an MI6 radio engineer named Harold K. Robin was dispatched to New York City.

Harold K. Robin, the MI6 radio engineer who was tasked with the job of preparing the behemoth transmitter for England. Robin devised a way to increase its power to 600 kW.

For two months, he commuted daily to RCA headquarters in Camden. There, he studied the workings of the 500 kW beast, and supervised modifications to boost its power to 600 kW.

The 100 kW increase was accomplished by over-powering the three 170 kW power amplifiers for the base 50 kW transmitter. For a time, this would be the most powerful broadcast transmitter in the world.

In addition to boosting the power, Robin made changes that enabled rapid tuning of the transmitter across the entire European medium wave band (526.5 kHz to 1606.5 kHz). The Germans used 612 kHz, 714 kHz, and 833 kHz for military broadcasts.

Robin made it possible to change the new transmitter’s frequency in less than a second, where doing the same with a conventional transmitter required changing crystals which took hours. Thus, the British could frequency-hop with ease.

The project was codenamed “Aspidistra” after a then-popular comedic music hall song, “The Biggest Aspidistra in the World.” Aspidistra was a houseplant that was common in British homes during the period. (Because it could survive long periods of neglect, the Aspidistra was nicknamed “the cast-iron plant.”) The song also had some bawdy connotations.

The common Aspidistra houseplant popular in England.

Aspidistra, soon shortened to ASPI, was placed under control of the Political Warfare Executive (PWE), a clandestine government group tasked with producing and distributing propaganda with the goal of weakening enemy morale.

By late November 1941, the first of three shiploads of transmitter parts departed for the UK. These included three antenna masts. One was lost when the ship carrying it was torpedoed delaying the project, while another mast was constructed and flown from the US. A site in Ashdown Forest known as King’s Standing near Crowborough, East Sussex (in southeast England) was selected for ASPI after much argument with the Air Ministry.

To protect it from German bombers, ASPI would be housed in a three-story building 50 feet underground. (The middle story was reserved for cable runs.) Once finished, the building would be topped by four feet of reinforced concrete, then soil, turf, and fast-growing trees for concealment.

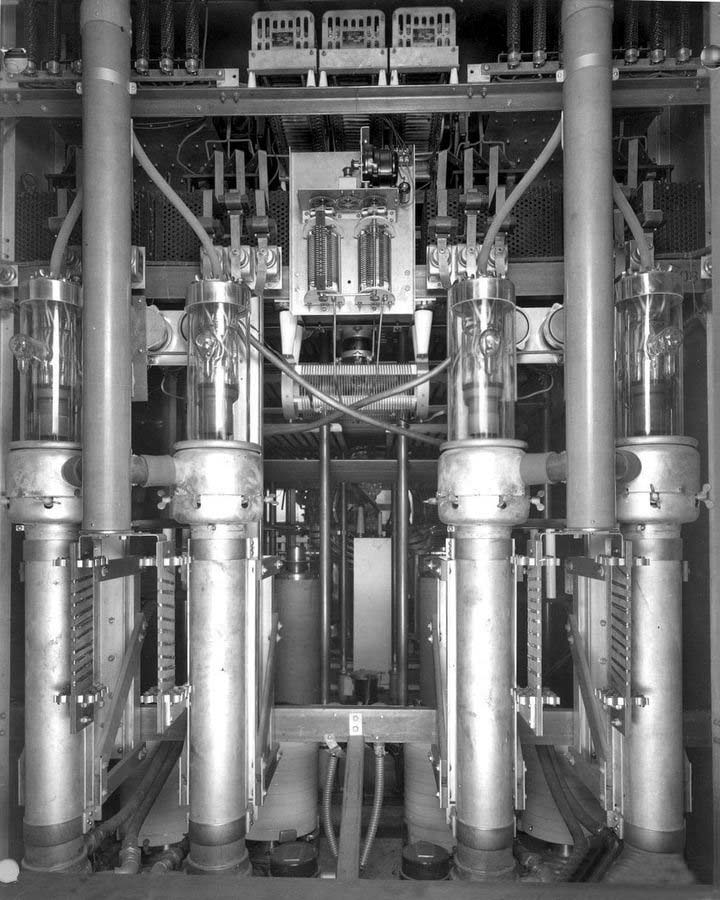

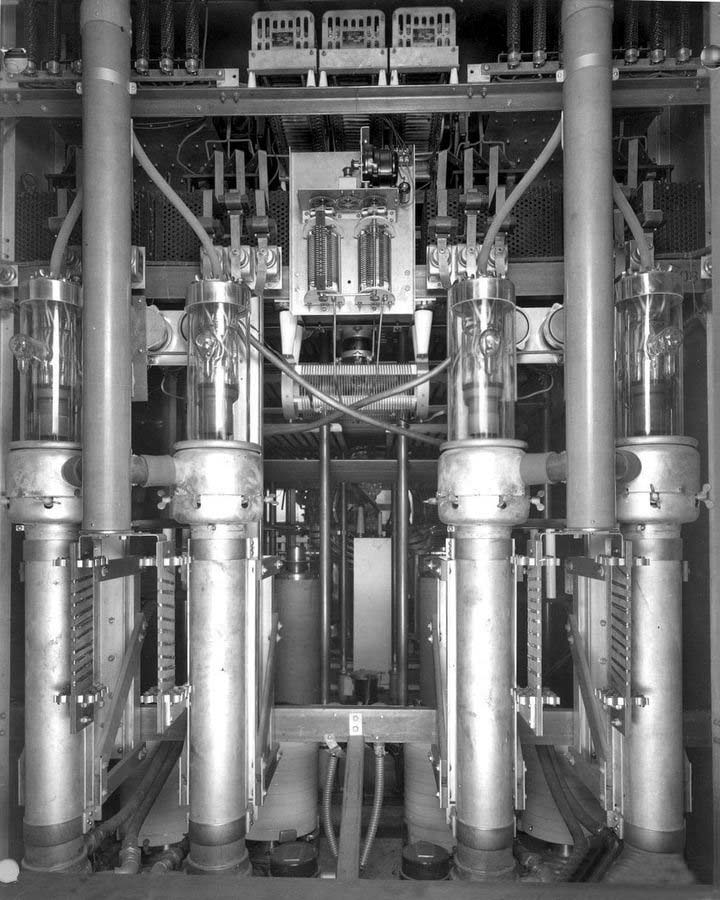

Technicians in charge of operating the 600 kW transmitter in its underground bunker.

The first order of business at the site was to dig the hole, which was accomplished by a Royal Canadian Army road-building unit who were idling in the area. They completed the excavation in six weeks with six bulldozers, explosives, and muscle. The structural steel, concrete, and other work was handled by some 600 civilian workers.

Like WLW, ASPI was built on a physical scale to match the incredible power it could unleash. The modulation transformers alone were each 10 feet tall and weighed over 15 tons. These were attended by more than a dozen water-cooled 100 kW vacuum tubes or valves (Westinghouse AW-220s, capable of 150 kW if pushed).

To carry away the heat generated by these and other components, ASPI piped the water to cool in concrete lagoons built into the structure’s ground-level roof.

Rooftop lagoons, or ponds, over which water heated by the transmitter was pumped to cool.

The transmitter was to be connected to the national electric grid. However, for 25 years, it ran from its own one megawatt power supply, driven by a 16-cylinder, 3,000 horsepower diesel engine.

Dedicated phone lines were run from ASPI to a remote studio in the village of Milton Bryan, Bedfordshire, about 100 miles north. The aerial masts were arrayed as one broadcast antenna and two directional units.

The original notion for using ASPI was to drown out the German’s propaganda on their own frequencies with British propaganda. At 600 kW, it could certainly do that.

A portion of the 600 kW transmitter from the inside.

There was also the possibility that the ASPI transmitter might use its power to jam German broadcasts, which could result in the Germans jamming BBC Home Service broadcasts — something neither side had done. Hence, those ideas were tabled.

The BBC protested loudly and at great length on these issues when it first discovered that Aspidistra was being installed. Being the monopoly broadcaster in Great Britain, the BBC felt it should have control of the new transmitter.

The protests continued until May 1942, when an agreement was reached under which the BBC could broadcast its European service (news) at high power when ASPI was not being used for other purposes.

Despite this reconciliation, the BBC retained its fear that ASPI might get them into a jamming war with the Germans.

The uses PWE had for ASPI were much more clever than simply jamming enemy stations. Simply put, PWE intended to impersonate German stations and broadcast “black propaganda” and “grey propaganda.” Black propaganda was a catch-all term for fake news, impersonation (or “spoofing”) of enemy stations, and other dirty tricks. Grey propaganda would deliver news and rumors about who was behind the black broadcasts or where the broadcasts might originate.

In comparison, the BBC’s straight news with a slant broadcasts were “white propaganda.”

The ASPI installation was completed in November 1942, just in time to support the Torch invasion of North Africa. Beginning on November 8, ASPI broadcast speeches by President Roosevelt and General Eisenhower.

The transmitter broadcast under the name Soldatensender Calais (Soldier Station Calais). “Calais” was a misdirection; Calais is located in France on the English Channel, facing Dover at the point where France and the UK are closest. Crowborough is perhaps 75 miles due west of Calais.

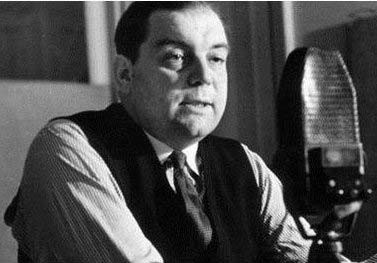

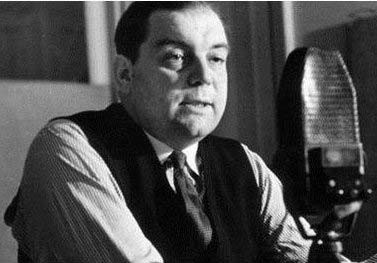

A German-born US citizen named Sefton Delmer was given the responsibility for PWE’s black propaganda broadcasts.

Sefton Delmar, who directed black propaganda broadcasts.

He was already well-practiced in black techniques, having operated several projects that specialized in them via radio broadcast and in print.

Delmer’s black broadcasting experience included shortwave broadcasts to German submarine crews via Deutscher Kurzwellensender Atlantik (German Shortwave Transmitter Atlantic), in which he and his German-speaking operators worked to destroy sub crew’s morale with rumors, innuendo, and lies.

ASPI came into full operation in January 1943. It was normally on the air from 6 PM to dawn. Delmer and his German-speaking operatives put Soldatensender Calais work on black broadcasts. Aimed at civilians and soldiers, the programming originated in the studios at Milton Bryan.

Legitimate news items were transmitted, along with forbidden jazz music to draw listeners. ASPI crews slipped in gloomy news when it happened — especially news that the government-controlled broadcasters ignored. They also broadcast fake news items about certain towns being evacuated, or counterfeit German banknotes flooding the country.

There was speculation as to whether soldiers still in the Fatherland were having affairs with deployed soldier’s and sailor’s wives, as well as whether the advancing Russian Army might be doing worse things.

The game became more serious when German military transmitters were shut down to prevent their serving as beacons for Allied bombers. The on-air staff at Milton Bryan impersonated bomber ground-control operators and sent groups of night fighters to the wrong sectors to make them miss incoming bombers.

At times, they used recordings of the real operators they’d made on a previous night to misdirect the aircraft. This was known as “Operation Dartboard.” Thanks to ASPI’s ability to drown out German broadcasters, Operation Dartboard was at times active when enemy transmitters were in operation.

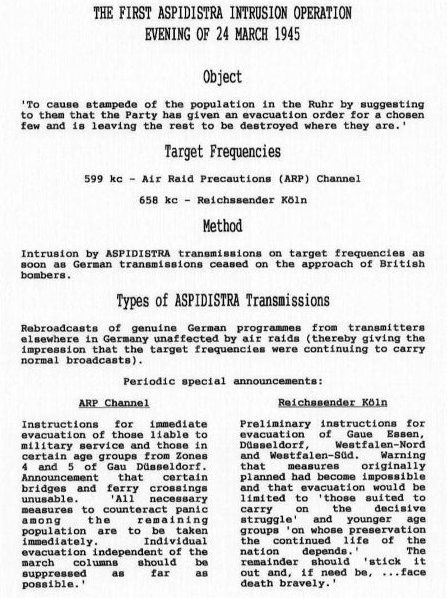

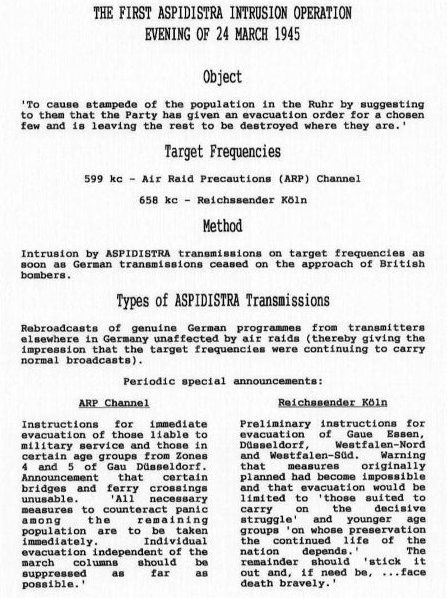

Outline for the first ASPI intrusion operation directed against Germany.

To combat ASPI, German broadcast procedures were changed; Soldatensender Calais copied the changes. For example, when the Germans brought in women operators, ASPI brought in German-fluent Wrens (members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, WRNS).

In November 1943, the Atlantiksender broadcasts were switched from shortwave transmitters to Soldatensender Calais. The change was made to reach more listeners, as the German population were more likely to have radios that received medium-wave broadcasts than shortwave sets.

On D-Day, Soldatensender Calais (by this time, Soldatensender West) broadcast fake information to make the German command think that the Allied invasion covered an even larger area than it did. At certain points, the German broadcasters tried to make announcements to the effect of, “The enemy is broadcasting counterfeit instructions on our frequencies. Do not be misled by them. Here is an official announcement of the Reich authority.” Soldatensender West sent out a similar message.

Half an hour after Berlin announced the allied landings, Soldatensender West returned to the air to announce, in English, “This is D Day. We shall now bring music for the invasion forces.” More news — most of it real but disparaging to the German listeners — followed.

When German prisoners of war and others were interviewed about the broadcasts, most admitted that they had been fooled by ASPI’s broadcasts. Both the fluency and smoothness of the announcers, along with techniques such as mixing real news with fake, and retransmitting or relaying actual German broadcasts, made the broadcasts sound authentic.

German soldiers were confident that, should an officer happen upon them listening to ASPI, they could always say that it was a real German station they were hearing.

Soldatensender Calais/West went off the air on April 30, 1945 without ceremony. The BBC operated the transmitter. The broadcaster happily used their 600 kW toy until 1982, when ASPI was dismantled and its towers demolished. The slack was taken up by a newer medium-wave transmitter in Oxfordness. NV